Windward Aviation’s owner Don Shearer started the company in 1990 and became the largest supplier of helicopter utility services in the state of Hawaii. Despite a long history of specializing in operations with the single-engine MD500 series, Shearer had long bemoaned not having the safety features that are offered by a twin and he discussed the recent addition of a BK117-850D2 to Windward’s fleet.

The Worry

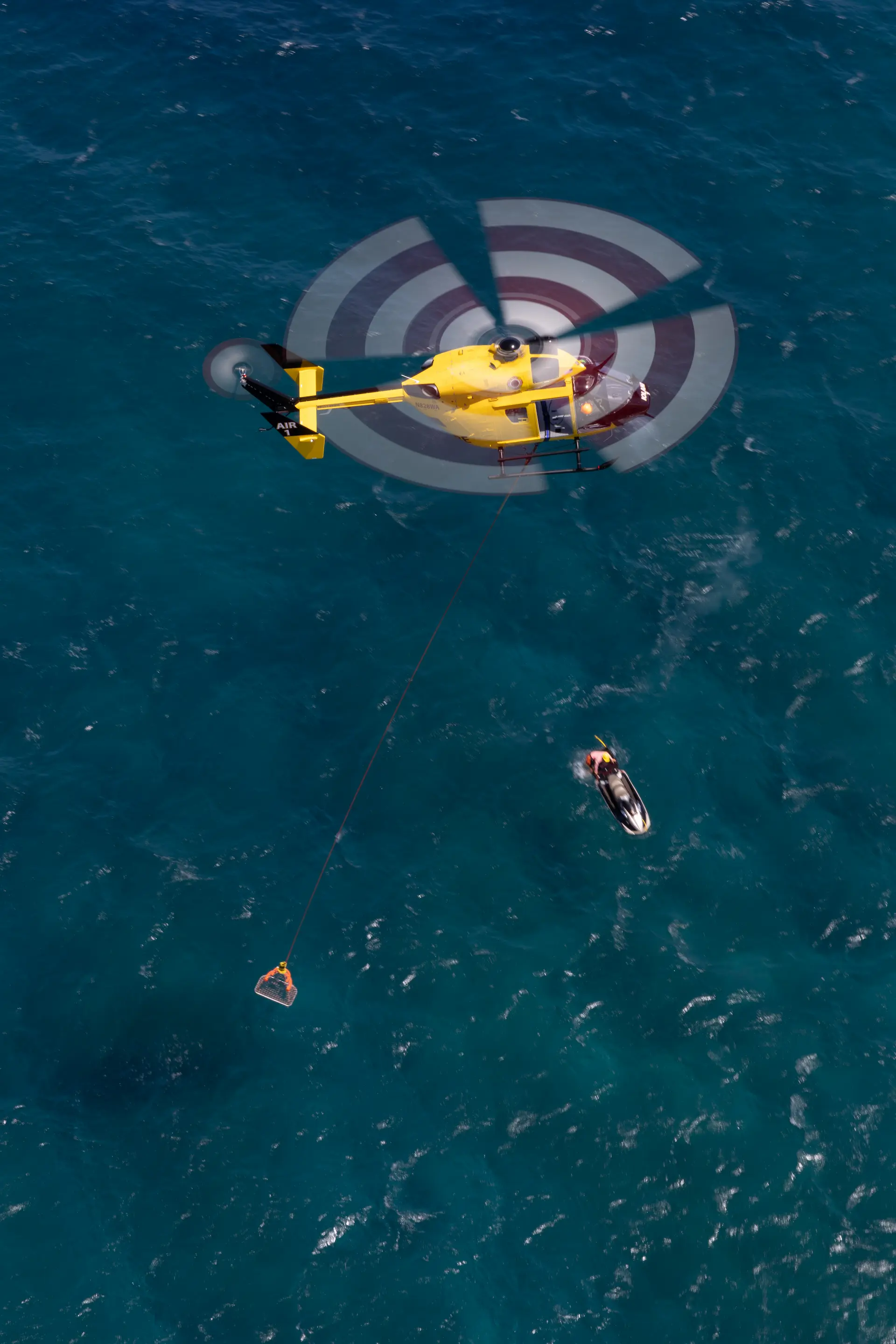

According to Shearer, Windward’s move to twin operations didn’t happen overnight, but developed over a twenty-year period. “Like everyone that does HEC (human external cargo) work, I was concerned about engine failure. You’ve got one or two guys on a 100ft line and you’re just waiting for something to go wrong, and I’ve worried about that pretty much since I started flying,” he stated. With well over 27,000hrs of logged flight time, A&P mechanic certification, an ATPL, instructor ratings for both fixed- and rotary-wing and time as an FAA production test pilot for Robinson Helicopters, Shearer is a vastly experienced pilot. He first started flying in 1978 and he recalled starting with police aviation in 1985, doing HEC work before anyone used safety equipment like bridles. He recounted, “We hired some mountaineering rangers who came down and taught us how to tie good knots and stuff like that, but I did all this HEC on marijuana eradication, and I was mentally destroyed by the whole experience.”

Once he started Windward Aviation, he flew countless HEC operations with the MD500s for the Maui fire department, on such missions as SAR, body recoveries and inserting firefighters into scenes that didn’t allow for landing. “I got pretty frustrated with it so about twenty years ago I went to the Fire Chief and told him that we needed to look at how we were operating.” By that time, night operations had been cut from the program, even though the aircraft had a NightSun searchlight. When you turn that on in inclement weather, you can get blinded and it’s a nightmare,” Shearer remarked. He added that since he had been in Hawaii, he knew of two Coast Guard helicopter crashes in which all occupants died, about eight military helicopter crashes and numerous civil crashes, all at night.

Challenge

The sparse population in many areas of the Hawaiian Islands makes for particularly challenging flying at night and Shearer explained, “There’s no such thing as night VFR in Hawaii. When you get on the north shore of any of the islands where no one lives, there are no lights and no celestial illumination if there’s an overcast. The only thing that’s kept me alive is that I’ve been able to fly with reference to the waves on the shoreline and ensure I keep moving,” he said, adding that during an offshore, night training mission with a pilot qualifying for the fire contract, the new pilot turned away from the lights and within seconds was in a ninety-degree bank, nose low heading for the water and Shearer had to recover the aircraft. “That’s when I realized that night operations were going to result in a rescue of the rescuers.” He also noted that he didn’t really want to carry out night ops in any case, as during NightSun operations it had been a frequent occurrence to search for supposed missing persons that where actually just out with their girlfriend, or some other reason that had nothing to do with hazard or rescue. Even in daylight, the mountainous terrain and coastal maritime environment create altitude, wind and weather challenges that can be extreme.

Shearer recalled saying in an official letter that if the fire department wanted 24-hour helicopter operations, the minimum safe equipment standard was the same as the Coast Guard. He specifically listed two engines, a two-pilot crew, hoist, auto-pilot with auto-hover and NVGs (night vision goggles), a configuration that at that time was simply out of reach of the county. “I sent the Fire Chief that letter requesting that we eliminated all night operations and he actually agreed with me, but we had just won a five-year contract with the fire department that required us to be a 24/7 operation.” That meant that in fairness to the other competitors that had bid the contract could not be altered, so the contract was re-bid with the exclusion of night ops, with day operations defined as takeoff no earlier than ten minutes after CMT (civil morning twilight) and landing not after ten minutes prior to CET (civil evening twilight). “I was happy with that,” Shearer advised, “But it continued to bother me that we were hauling the public and rescuers on 100ft lines under single-engine helicopters. I had to go through continual education of the department and several administrations until I finally got to Brad Ventura, the current Chief of the fire department. He’d spent a lot of time in rescue, knew all of the risks and had heard all of my conversations about what we’re exposed to. If the damn thing coughs, sputters or quits, we’re dead!”

With all that in mind, Shearer and daughter Nicole helped educate the department developing specifications for a new contract, including using a twin-engine machine. “We looked at all the twin-engine machines that were out there and went for cost first and then performance. Many don’t give adequate single-engine performance and to get one that does, you have to pay for it. Then we came across the BK117, and in particular the -850D2 version developed by Airwork in New Zealand.” The D2 is an STC- modified, re-engined BK117-B2, with two 850hp Honeywell LTS 101-850B-2 engines replacing the original 750hp -750B-1 units and Shearer advised that a good, clean example could be obtained for about US$2 million, but outperform many far more expensive types. “When we compared price and performance the BK kept rising to the top,” he concluded. It took some time to get the twin-engine machine approved as Shearer first had to convince the fire department, the Fire Commission, the council, and the mayor’s office. “When the contract came out, it was awarded on 1 July 2021 for one year using the MD500, and from 1 July 2022 for another four years with the BK, and we were the only ones that bid on it,” he explained. “I think that was because the barrier entry requirements were quite stringent. You had to have a covered facility on Maui, pilot experience and mechanic experience requirements were appropriately high, and the operator had to have been in business for five years providing SAR operations in the state of Hawaii.” The original pilot requirement was 5,000hrs total helicopter time but that was subsequently reduced to 3,000hrs when the provision of training time was doubled.

Kiwi Connection

The initial year with the MD500 gave Windward time to find a suitable aircraft, get it to Hawaii and get it to the required configuration. Shearer already had good leads on a couple of examples and ended up acquiring a used example from Haverfield Aviation. “Nicole and I developed a timeline for acquisition, paint, avionics and hoist. We set out a six-month schedule, gave it to the fire department and we hit every single target time, exactly as we had predicted. The Windward BK was the first that Haverfield had bought and twenty-thousand man-hours had been spent on bringing it up to a virtually brand-new standard, so Windward obtained a remarkably pristine example. “Virtually every hose, wire, nipple, fitting had been changed so we got a really clean helicopter,” commented Shearer. Windward spent another $500,000 on the purchase, provisioning for, and fitting of a hoist. “Then we had to get some training because no one here had any formal training on a BK, and we got some excellent factory training from New Zealander Grant Smith, who is a really solid, professional guy and an all-around good dude.”

Public use

Windward’s BK can be operated under public-use provisions, which require a minimum 90-day exclusive use contract with any state, county or local municipality and an annual declaration to the FAA. “This is on exclusive use for the County of Maui Fire Department so that aircraft sits there with a pilot and maintenance every day of the year, solely for their needs and we’ll be airborne no more than eight minutes after the fire crew arrives, and often within only two or three minutes. We do all the search and rescues, all of the body recoveries and all the aerial firefighting. We’ll respond to motor accidents, but only if they’re where they can’t access the scene on the ground, and we can fulfil some administrative flight needs if necessary. We can load it up with nine guys in the back, one up front, get out of here still below max’ gross weight and get to any of the other islands,” said Shearer. Firefighters that work with the helicopter come from ‘Rescue 10’, a fire department unit of role specialists that specializes in difficult access and extreme scenarios. The helicopters do not offer an EMS service but recover victims and deliver them to the next higher level of care as quickly as possible. Shearer explained that, although there is an operating EMS helicopter provider, the restrictions on where they can land mean that Windward usually recovers the victim and delivers them to the EMS machine at one of its designated landing zones.

Operating under public-use allows a critical and unprecedented modification to the machine, swapping the right-seat pilot-in-command (PIC) position over to the left. Shearer stated that he had been stressed over the right-side PIC because it required the pilot to rely on a rear crewmember for precise guidance in positioning the machine during HEC operations, something entirely unfamiliar to the highly experienced longline flyers. “Putting the pilot in the left seat is a non-STC’d configuration so we can’t operate it under part-135 or part-133, but it complies with public-use and we have the manual hydraulic release on the left collective, with the press-to-release on the cyclic and now we don’t have to impose the stress and responsibility of positioning the aircraft onto the firefighters or crew in the back. I spent my first 18 or 19 hours in the right seat, and I hated it, but once I flew it from the left, I knew we could do this.” As far as Shearer is concerned, aside from the peace of mind that comes with the massive increase in safety, the most impressive aspect of the BK117 is the huge power margin that it brings to the table. “We have such a power reserve that we’ve never had before. Let’s face it; in a 500 with a full tank of gas and four guys, you don’t have much left. We operate from sea level to the tops at around 10,000ft and with the BK you look down and see you’re only pulling around forty percent torque,” he enthused.

Hoist Training

None of the Windward pilots were hoist trained, so another round of training was necessitated to teach them operations with the Breeze-Eastern 600lb hoist, which can operate at double speed with a 250lb load or less. In addition, six firefighters have been trained to be competent in hoist operation and by incorporating the firefighters into the 25hrs hoist training for each of the first four BK pilots, the fire department scored more than 100hrs of free training for their men. The type training and hoist training was all at Windward’s expense as a part of the contract, with Shearer explaining that he had wanted to give something back because of his strong desire to see a successful move to top-level twin operations. “I wanted the peace of mind that we could all comfortably and safely fly this helicopter with its two engines, two hydraulic systems, two electrical systems and simplified fuel system. We respond to an area of more than five thousand square miles, over the five main Hawaiian Islands and up to four miles off their entire coastlines. We’ve been doing this for years with the 500s and their one engine, now we’ve got this thing and what a relief that is!”

Shearer describes Hawaii as a wild place, with many injuries sustained by overly adventurous but under-skilled or overweight and unfit tourists who attempt activities far beyond their capabilities or get lost. There is also around thirty knots of wind almost every day frequently blowing people engaged in water sports and boating, well offshore. The Windward crews have alerts on their cellphones whenever a 911 dispatcher starts typing, so even before the radio goes off, they are often aware of a probable callout. “We get exposed to a lot of searches and we’ll search for 72 hours for a person in the water. That happens anywhere from seven to fifteen times a year and often we’ll find nothing, or just a piece of their board, sail or bathing suit. It’s gnarly, a lot of people come here and die. There are shark attacks and although the victim is usually recovered to the beach, we will fly shark patrols afterward. It’s not uncommon to get a call to search for a missing dementia patient and we’ve had a busy time with fires this year. Someone lit a trash fire that got out of control, and it burned about 5,000 acres, but there was no access to it by anyone on the ground so the helicopter was the ideal firefighting asset, and we probably flew about 100 hours on the BK on that fire alone.” Windward runs a 250-gallon Water Hog bucket on a 50ft line for firefighting, which the BK can fill and lift – even with a full tank of fuel – from the closest water source, whether it be ocean or pond.

Utilization under the fire department contract is understandably highly variable and Shearer reported that he has flown on as many as five calls in a single day, while at other times there can be little or no activity for several days on end.

Operating Safely

He estimated that since the twin’s contract commenced almost one year ago, the BK117 has amassed around 280 flight hours. The addition of the BK is not expected to result in any increase in workload but will greatly increase operational safety, capacity, and capability. Nevertheless, Shearer states that he will never let his guard down and that he flies with the understanding that a helicopter will try to kill you every second that you’re in it. “I never totally relax and it’s why I never let any music be played on the aircraft or allow any cellphone use. You have to be in the here-and-now, listening the whole time.”

He always starts the helicopter with his helmet off and flies with the door off, so he can hopefully detect any unusual noise that may be a sign of impending mechanical issues. “Helicopters all talk to you, and you have to be smart enough to pay attention,” he commented. The one thing Shearer particularly dislikes about the BK is its rigid main rotor system and how it is affected by the gust spreads in Hawaii, but he is effusive in his endorsement of the aircraft’s overall design, build quality and structural solidity. “Once you get through translation, the thing is smooth as hell and fast. The hydraulics are nice and it’s comfortable to fly, with its adjustable seat and pedals.”

Maintenance

Maintenance is carried out predominantly at night to keep the aircraft available and under the fire department contract Windward has just one hour to replace the BK with another helicopter if it goes out of service. Reliability on the BK has been excellent however and only very minor issues have reared their heads so far. One of those was a chip detector failure but a parts helicopter was bought very soon after the BK entered service to provide a ready source of many spares and reduce wait times for replacement parts.

Summing up what the BK brings to the fire department contract, Shearer concluded, “This aircraft enables the fire department to respond to remote areas that require multiple man-hours in support of operations, anywhere in the county. We’ve got it here now and I feel that I’ve got to the point in my life that I can retire, because I’ve done what I said I was going to do. We have a level of professionalism, competence and confidence in the equipment and the program that I feel really good about having got it over the finish line. Even if it costs us a little bit more and we don’t make as much profit as we did with the MD500 – which we don’t – it was worth it, because we’re going to come home at the end of the day.”

HOME

HOME