The requirements for helicopter pilots appear to wax and wane, largely depending on the airline industry needs and general economic health. Declan Daly examines the current pilot shortage, its causes and progress.

Like the setting of the sun and the rising of the moon, conversation around the global supply of helicopter pilots follows cyclical arcs between boom and bust, alternating from surplus to under-supply. In recent years, the conversation has been predominantly US-centred, with airlines swallowing huge swathes of pilots from the rotary wing industry - especially those from the ‘usual’ pipeline of the US Army thanks to a number of bespoke schemes smoothing the pathway from 'Black Hawk to Boeing 737'. With that particular period seemingly drawing to a close, a reassessment of the global state of affairs is in order.

Taking the starting point that, in my experience, crews on the line have always been more keenly sensitive to the depth of the piloting pool than those working at an organisational or industrial level, for this article, I have used a survey to attempt to get a view of the worldwide level of confidence that crews have in the current and future levels of pilot availability in the helicopter world. The 'canaries in the mine' are the flock all around you, after all. Ultimately, ‘where do we stand today?’ is the starting point, but seeking an awareness of where we will be in the future and how attractive the industry is to the next generation of future pilots is important too.

The Headline Figure – Industry, we have a problem

This would seem to be a fairly damning figure, with over 80% of respondents seeing that the industry as it currently stands is understocked with pilots. However, when projecting forward and allowing a five/ten-year period for someone to decide to enter the market, train, build some experience and get a living wage job, things become even more stark:

In this case, close to 90% of the surveyed helicopter pilots worldwide, military and civil, and across different sectors, foresee a shortage of pilots available to the industry. To get a bit more of a nuanced view, let’s discuss the survey and its results.

Strengths and Limitations

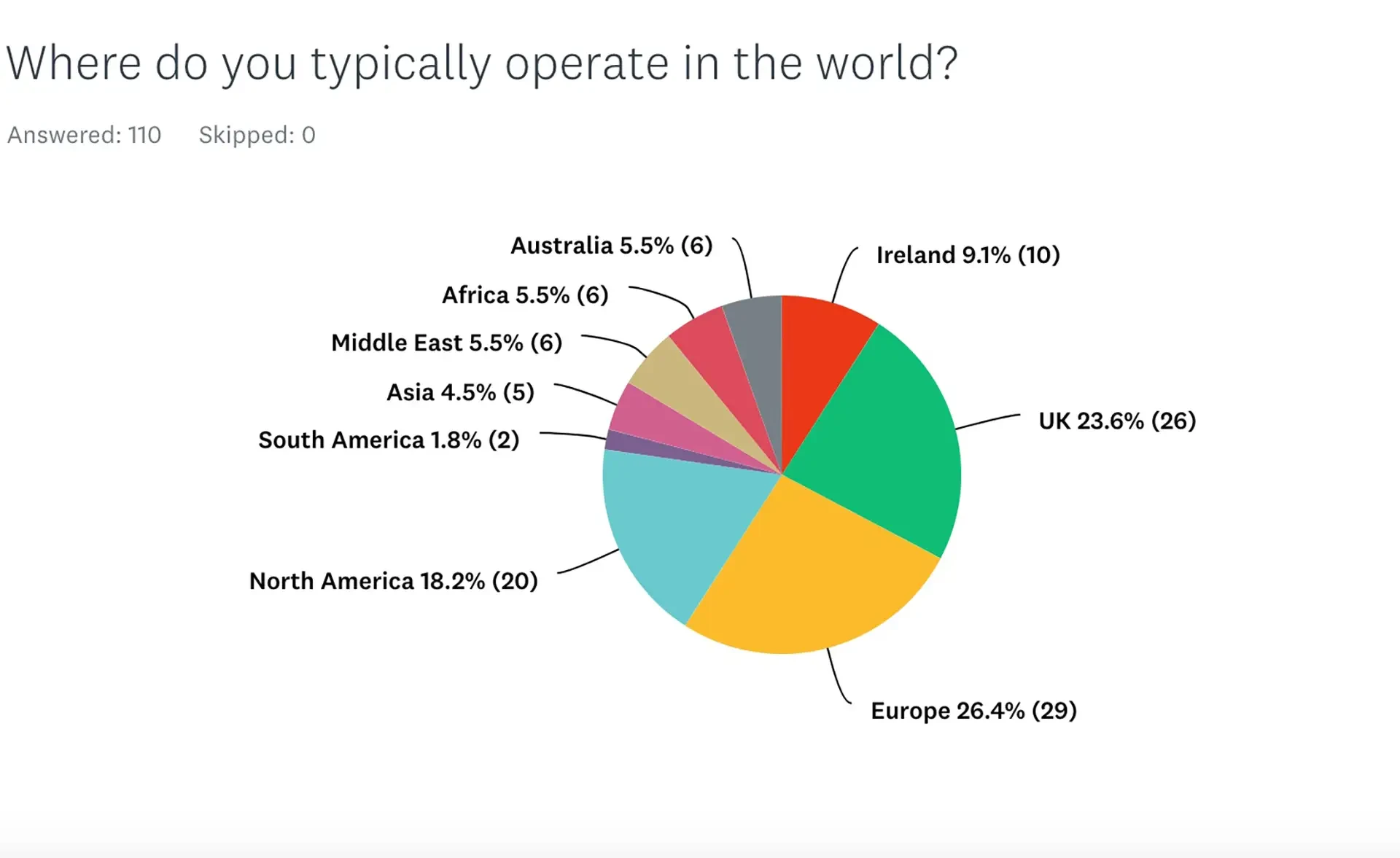

Were this an academic piece, I would, at this point, have to outline the methodology and limitations behind such figures, and that seems fair. I used a well-known online survey tool to collect the data and distributed it over Linkedin. I chose to do so as my primary goal was to allow pilots to answer honestly, anonymously and easily. This meant not going through companies or military organisations where, even with the best will in the world, there may have been a fear of internal oversight. The strength of this approach is that it allows for a truly global reach and one where anonymity protects the ability of people to be as clear and direct with their answers as they may wish. The survey was designed to be answerable in about 2-3 minutes at a minimum but less than ten at the most in order to maximise the number of respondents (people tend not to answer long surveys unless they are really passionate about the subject which can in itself skew the results).

In terms of limitations, the survey was dispatched through my own personal account, which may have limited the initial visibility only to those who know or follow me, and this may have been reflected in the sectoral results. In addition, while English is the language of aviation, it may not be the first language with which people engage with social media, further limiting the pool of respondents. Lastly, by virtue of being short and aimed at a broad audience, intra-sector nuances may have been lost. In conclusion, plenty of research questions were left for other people if they so wished!

Nevertheless, 110 respondents participated in the survey with a sufficiently international and inter sector flavour that I do believe the survey gives a useful indication of what we can expect to see in the helicopter world over the next few years.

The ‘other’ responses included Law Enforcement, Flight test, Ag, VVIP, VIP, Customs and Training/CAT.

Sectoral distribution

Overall, the picture has been consistent, but some sectors are now, and expect to be in the future, under more pressure than others, as shown below. Critically, even those sectors that are currently divided on the existence of a shortage still expect one to come down the road. What this means is that while some areas may be able to use the time available to prepare and seek out new blood, other areas (100% of military pilots for example) are living the problem right now with all the work/life balance, commercial and flight safety issues that automatically follow on from that.

It is worth noting here that with so few responses from firefighting pilots, while their responses were coherent with the whole, the sector-specific picture may not be as accurate. Nevertheless, we can look at the relatively larger numbers of military and SAR/HEMS pilots to assure a consistent picture and draw some conclusions based on their comments on the causes and best solutions to the problem.

Of 102 responses to the Question “If there is a shortage, what in your opinion has been the main cause?’” 43 (42.15%) respondents

highlighted cost as being the most significant barrier to entry. 11 (10.78%) cited a lack of ex-military pilots entering the civil market

and 8 (7.84%) cited an age/experience gap as being responsible, whereby older and more experienced pilots retire or otherwise leave but are

not replaced.

Military pilots – insufficient supply in the parallel pipeline

‘Bad recruitment plans, low salaries’

Military Pilot, Europe

‘Fewer leaving the military and fewer civies coming through.’

SAR/HEMS pilot, UK

‘Lack of former military pilots joining civil helicopter industry.’

SAR/HEMS pilot North America

Taking these out of order, the simplest one to explain away is the apparent lack of military pilots joining the civil sector. In the same way as there was a changing of the guard, as it were when the bulk of the Vietnam War and Cold War era pilots retired, a similar event is currently taking place. Large military fleets with a correspondingly large number of frontline crews, operational training squadrons and training pipelines, along with the more hidden surplus of pilots in staff appointments, have largely become a thing of the past. Even the GWOT era staffing levels have dropped in most militaries in those countries that participated in those conflicts. As an example, the UK’s Puma fleet, which originally numbered forty-eight aircraft and is now down to seventeen, is due to be replaced by as few as twenty-eight helicopters (and, quite possibly, half that number...). Correspondingly, the overall number of pilots required, and therefore trained, is lower. This picture is apparent globally, with numbers of pilots leaving the military being, in absolute terms, lower as shrinking defence budgets of the post-Cold War 'Peace Dividend' catch up to retirements today. However, this does not imply that all is rosy for the militaries of the world, which are, in many places, struggling to recruit and expand. In relative terms, greater numbers are leaving and likely to leave as the same budget cuts that shrank fleets also hit military Ts&Cs hard::

‘Shortage in senior P1’s due to wages not being aligned with civilian sector jobs. Defence Forces new pension for post 2013 individuals makes it untenable to stay. For the Air Corps, the first look at this will come shortly as those who joined in 2013 will soon be at their 12 year contract end date. I would envisage most will leave’

Military pilot, Ireland

While this respondent highlights an Irish-specific problem, it does reflect the global military pilot position that their sector will be experiencing a shortage now (100%) and for the next ten years (92.3%). In short, the civil sector will not see shortages addressed by experienced pilots retiring from the military any time soon.

With many military organisations seeking to expand to meet the current security environment, retaining experienced crews is essential, and those crews have offered the means by which that may be achieved:

‘Raising salaries could be a short time solution, then the workload should be decreased.’

Military Pilot, Middle East

‘Military pilot pay needs to match private sector in order to retain pilots. Current service commitment scheme not sufficing as an alternative.’

Military Pilot, Ireland

Uniquely, state agencies may be in a position to pay their way out of the problem or at least use increased pay as a means of holding on to

pilots for a few more years while a new generation is in training and gaining experience. In the event that militaries worldwide are

successful in stopping their own brain drain, they are still however facing a projected shortage if they cannot increase their training

capacity when 100% of respondents are saying there is already a shortage.

‘The military provides public security. If you have a pilot shortage, or if you have incompetent pilots, the lives and public resources will be at risk.’

Military Pilot , Middle East

‘It is less about the actual numbers of pilots, and more that the people present are struggling to achieve the necessary experience.’

Military Pilot , Ireland

Shrinking force structures over the years also ate away at the capacity to internally regenerate through training new crews. With less frontline units being fed, the fleet sizes and instructor numbers in training institutions also shrank. This means they are not there now when needed, nor is the flexibility there to draw instructors from already stretched operational units. This could present itself as a business opportunity for civilian training providers, but as they are likely to be drawing from the very same pool of personnel, it may not actually help military retention at all. Viewed as a closed circle, the military sector's pressures are surprisingly illustrative of the rest of the industry. One answer for such organisations may be to seek to increase the amount of reservists who choose to stay 'somewhat in uniform' after leaving fulltime employment with the state. In many countries, this will require employment protection, licence protection and other measures to make it a feasible option - including fair consideration of any accrued military pension. Legislation in this area may be the gentlest thistle to grasp when compared to the security implications of not being able to fly your aircraft in a time of heightened need.

SAR/HEMS – A perception gap on rewards

‘Low pay: HEMS now wants the full package in a pilot, IR & NVIS operating a complex type. These pilots can earn a lot more in other

sectors, however employers considered the job provides more in job satisfaction so this should count as salary shortfall.’

SAR/HEMS Pilot, UK

‘The industry has to mature and recognize that they can keep their talent and foster more. But it's 2025,we want to live as well, we want to see our families, and have an active lifestyle all at the same time as being able to pay our bills. Right now, more pilots I know are having to choose one over the other.’

SAR/HEMS Pilot, North America

It is axiomatic to say that if a SAR or HEMS service is shuttered due lack of crews, then lives are put at risk. The

consequences of the helicopter not being there for someone when needed can indeed be fatal. Despite this, it does appear that the

particular requirements of the job that are over and above entry level positions are not always being recognised. In this sector of the

industry a pilot must turn up for interview with a CPL at the very least along with an IR and very often a multi engine rating under their

belt. It should surprise no one to say this isn’t cheap. As seen in the quote above, there can be a disconnect between the view of the

hiring organisation who may see live saving activities as a reward in itself, and the views of the pilot who sees it as a job that they

need to pay the bills (including, perhaps, loans drawn down to pay for all the aforementioned qualifications). The job satisfaction of SAR

and HEMs flying is unquestionable, but we are living through a cost of living crisis, and it such high levels of satisfaction are a

perk of the job, not a replacement for cash.

‘Reduced numbers leaving the military and strong offshore oil and gas sector’

SAR/HEMS Pilot, UK

In the UK this seems to have come to the fore when the both the number of ex-military pilots dropped off and when the various HEMS operations began to adopt more complex twin pilot machines. In a previous era, it had been easier for ex-military pilots with service pensions to take up HEMS positions on wages which were below the industry average. Similarly, SAR trrained pilots could leave the military directly into similar civilian jobs, where the pros of staying in one location vs seeking employment elsewhere may have offset the pay package, especially as they would still be on more than their former military salary. It is also worth considering that many of this past generation would have been able to afford to buy a reasonable family home - but the inflation in house prices makes that far harder for current aircrew. With some HEMS groups asking for a frozen ATPL(H) and 1000hrs flying time for co-pilots, it is little surprise that suitably qualified crews have taken those hours to oil and gas rather than accept comparitively low pay. In SAR, the supply of ex-mil pilots is essentially exhausted (and this is increasingly the case Europe wide) and so the wages paid must reflect the competition in the industry.

While all would acknowledge that 24/7 is the nature of the beast for such services, there were many responses to the following effect:

‘Some bases cannot recruit because of punishing 12 hr day/night rosters and a 4/4 roster without adequate sleeping facilities’

SAR/HEMS Pilot , UK

‘The industry is becoming less attractive. Salaries are not competitive and working conditions are horrible. Poor salaries, Unstable jobs, no career progression, no benefits, etc…’

SAR/HEMS Pilot , UK

‘Stagnant Pay, The airlines and their associated unions have recognized the need to increase pay to keep their experienced pilots. Myself and too many of my (20yr plus experience) colleagues just want to leave the industry altogether for better pay and/or schedule.’

SAR/HEMS Pilot, UK

Clearly there is a reward issue in parts of the SAR/HEMS world. When pilots are viewing their fixed wing counterparts on regular schedules

and what may seem from the outside like less tasking flights getting greater financial and other incentives to stay in the role, and

with 89.4% of the sectors pilots forecasting a continued shortage of pilots in the next five to ten years, it is important that the

agencies providing such services address the perceived difficulties of staying

In the job over the long term so ‘that others might live’.

Future flyers – knowledge gap and barriers to entry

‘Young people are not as interested in joining aviation as a pilot as they once were.’

Military Pilot, Ireland

‘The younger generation are realizing that it’s not worth the stress. The workload is more than the pay and it’s outrageously expensive to

train as a pilot. When you can sit in front of your computer invest your time in AI and crypto and you will make money.’

Oil and Gas Pilot, Middle East

There are two strands to addressing the envisaged shortage. One is retention of existing crews; the other is to attract and train a new

generation of pilots. Commercial Air Transport flights, at the very least, are unlikely to go unmanned any time soon, and extending single

pilot ops is already meeting justified resistance in the airline world and will likely meet the same resistance amongst the heli industry,

so jobs are likely to endure. With the opinion that younger people are less willing to enter the industry being somewhat borne out by the

ageing demographics in terms of the global pilot population, and an inherent gap in mass training due to school closures during the covid

pandemic and previous military drawdowns, it would seem a lot is riding on those who are eligible to start their aviation careers in the

next few years.

While those within the industry will rightly focus on what they see as impediments to joining, the fact is they joined the industry. The factors they now experience as negative may not have been visible to them at the time. This leaves the question of what is visible that is stopping school and college leavers from grabbing life by the collective…

To get a snapshot of the reasons why, I sent another survey to an Irish secondary school. This school was not randomly chosen – the principle has a PPL(A), and previous students have included male and female pilots of both the fixed wing and rotary persuasion in both civil and military fields. In that regard, students there should at least see a career in aviation as achievable and on their radar, so to speak. The survey was sent out to the senior cycle of students (~ 200) and received 25 responses. Regrettably, 88% of respondents had no interest in a career flying helicopters. The fact that women are more likely to respond to surveys than men was evident here, with 14 of the respondents being female, of which two were interested in becoming civil pilots. Of the male respondents, one respondent was interested in becoming a military pilot. As aviation, in general, is male-dominated, this may have had an effect on results but also gives a good impression of how to target that demographic – after all, women make up 49.6% of people globally, so they represent the biggest single opportunity to recruit from sources outside of those which may already have reached saturation.

The reasons given by those who did not see themselves seeking a career in helicopters, however, are not the same as those submitted by those already in the industry.

‘This job doesn’t attract me.’

‘Female Student’

‘The risks of dying and fear of heights.’

‘Male Student’

As solid ‘No’s’, these were representative of the answers received and, I mean, fair enough – it’s not for everyone. In terms of offering wiggle room where, as a group, we can attract more applicants, some of the other answers were informative:

‘Not knowing much about it’

‘Female Student’

‘Danger and being away from home.’

‘ Female Student’

A perception that helicopter flying is more dangerous than it actually is pervaded the answers, but also it was apparent that there was

little knowledge on how to become a pilot:

What this shows is that even in a school where some level of aviation history exists, students don’t actually have the information available

to them en masse to choose it as a career. Interestingly, where students were asked if the option to become a pilot was included in the form

they fill in with their desired college courses before their final year school exams, the numbers shifted dramatically (the option of

including a degree as part of the package actually acted as a disincentive by about 10%).

What we can take from this is that, given that students are less likely to personally know people who are pilots due to the current shortage and the age gap, we as an industry have to find a way to deliberately put reliable and realistic information in front of them that makes the perception of danger more contextualised and the pros and cons apparent. Even with this very small group, the indications are that the payback in numbers will be there.

Cost factor

‘Training costs are too high thus preventing so many from starting or finishing. Salaries and industry fluctuations also make the risk/reward too high for those already on the margin.’

Oil and Gas Pilot , UK

‘The price of initial training’

Oil and Gas Pilot, Europe

The other main barrier to entry is, of course, the sheer cost of entering the market if funding it yourself. Fully 42.15% of the respondents to the initial survey identified cost as the main causal factor in the current and projected shortage. This is unsurprising as more and more jobs now require a multi-engine rating and IR at point of entry. These ‘extra’ courses drastically inflate the already high training price compared to a single engine turbine rating, a CPL and as many hours as you can get early on.

In summary – Solutions

‘Invest in younger pilots, treat them well, and you'll improve retention.’

Utility/Charter Pilot, Africa

From the respondents’ comments, a great degree of consistency was apparent on what may resolve the current issues. In terms of reducing training costs, government subsidies to schools, cadet programmes and an end to self-funded type ratings emerged as the most popular options.

It was also identified (and cross-checked with the school survey) that making the career visible through the same means used for other careers in each country was important to reach more prospective pilots.

Critically, for retention, an increase in Ts&Cs will be required—not just pay but also physical working conditions, which will have to improve towards airline standards to compete with fixed-wing organisations.

The concept that ex-military pilots will be available to the market in significant numbers is one of a bygone era. Even in another twenty years (global security situation permitting), the pilots exiting the armed forces will not have old-school pensions but rather less salubrious modern ones. Their numbers will not be sufficient to affect the remuneration packages or numbers required by the civil industry writ large.

Respondents, civil and military, also identified a lack of investment in junior pilots development – both at a company and industry level, but also at a crew level. The image of the ‘always right’ old captain has not, unfortunately, faded away. If pilots are in short supply however, there are real needs apparent to mentor and support newer pilots in order to fill the gaps left by old sweats hitting retirement age.

If the numbers in these surveys are indeed a real statement on the state of the industry then it is apparent that all parties have an interest in seeing things change. Without identifying and enacting solutions, flight safety and commercial risks will begin to manifest themselves. While some of the solutions identified do include a financial outlay, these are all small amounts when compared to the revenue lost through penalties for downtime due lack of crews. The company that invests in its crews may well be the one that wins contracts in the future.

‘Encourage lower time pilots to apply for roles with the opportunities to develop and grow.’

Utility/Charter Pilot, Australia

HOME

HOME