I didn’t reinvent the wheel, nor did I develop any groundbreaking new flying techniques for mountain pilots. What I did was gather existing knowledge, combine it with my own thoughts and experiences, and turn it into a structured mountain-flying resource for every pilot curious to learn more.

Mountain flying often sits as an “add-on” to regular operations. Knowledge is passed along internally through company training, and sometimes pilots are sent to a mountain course to learn the basics. That’s a start — but far from enough. Talking openly about mountain flying is not just useful, it’s vital for our industry.

So what is it really all about? Why should mountain flying get the space it deserves? The answer is simple: because it hides challenges and traps you cannot safely master by trial and error. No pilot has enough lives to make every mistake on their own. Mountain flying is more like learning a new discipline; becoming a flight instructor, earning an IFR rating, or flying external loads. It requires structured learning and focused practice. It is also a perishable skill

Some areas deserve particular attention. Let me highlight a few of them here:

Performance – Keeping the Balance

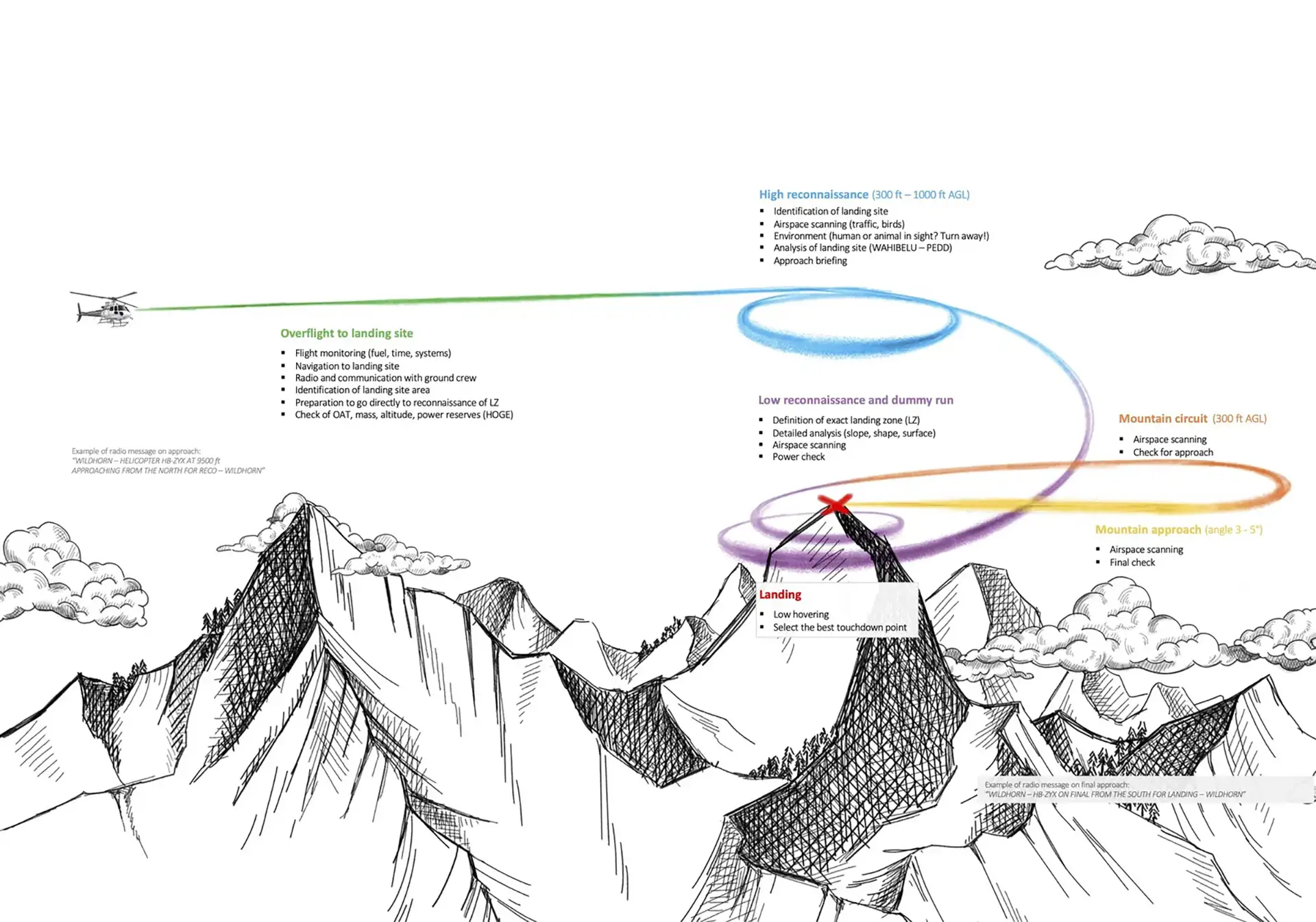

Performance is the one constant you can’t argue with. In the mountains, it decides everything: whether you can lift out of a site, whether you still have power for a go-around, or whether a light gust pushes you into settling terrain. At lower altitudes, with cooler air and plenty of space, you can sometimes get away with cutting corners. In the mountains, you can’t. High density altitude, limited manoeuvring room, confined areas; all of it strips away the comfort zone. I’ve seen situations where the numbers said it was just within limits, but standing there with the rotors turning, you could feel the margin was gone before you even raised the collective. That’s the kind of call you can only read between the lines in a performance chart.

Managing performance isn’t about filling out a graph in the handbook. It’s about turning numbers into judgment. It’s the ability to see when

something looks like a “go” on paper, but in reality is already a clear no-go. A glacier isn’t just a flat white surface; it’s elevation,

slope, air density, and load case all layered together. An alpine forest clearing isn’t simply a confined spot at 7,000 feet; it’s an

approach where Out of Ground Effect (OGE) hover may already be at the last notch of available power, and where the go-around decision has to

come earlier than usual.

Margins are like currency, and in the mountains, you can spend them fast. The pilots who stay out of trouble are the ones who 'fly defensively', and protect those margins as if they were their last litres of fuel. Because sometimes, that’s exactly what they are.

To make those invisible lines visible, start with a few simple steps:

- Numbers don’t lie – run the calculations and know where you stand before reality proves what’s possible and what’s not.

- Read the field – study wind (look for wind direction and strength markers and read the terrain), ground effect, approach path, and escape routes; every factor shapes your true margin.

- Adapt your tactics – the tighter the margin, the simpler and more conservative your operation needs to be.

Still unsure what that looks like in practice? Then it’s time to dig deeper into the Mountain Flying Handbook, or better yet, strap in for a dedicated mountain flying course.

Weather – Working With It, Not Against It

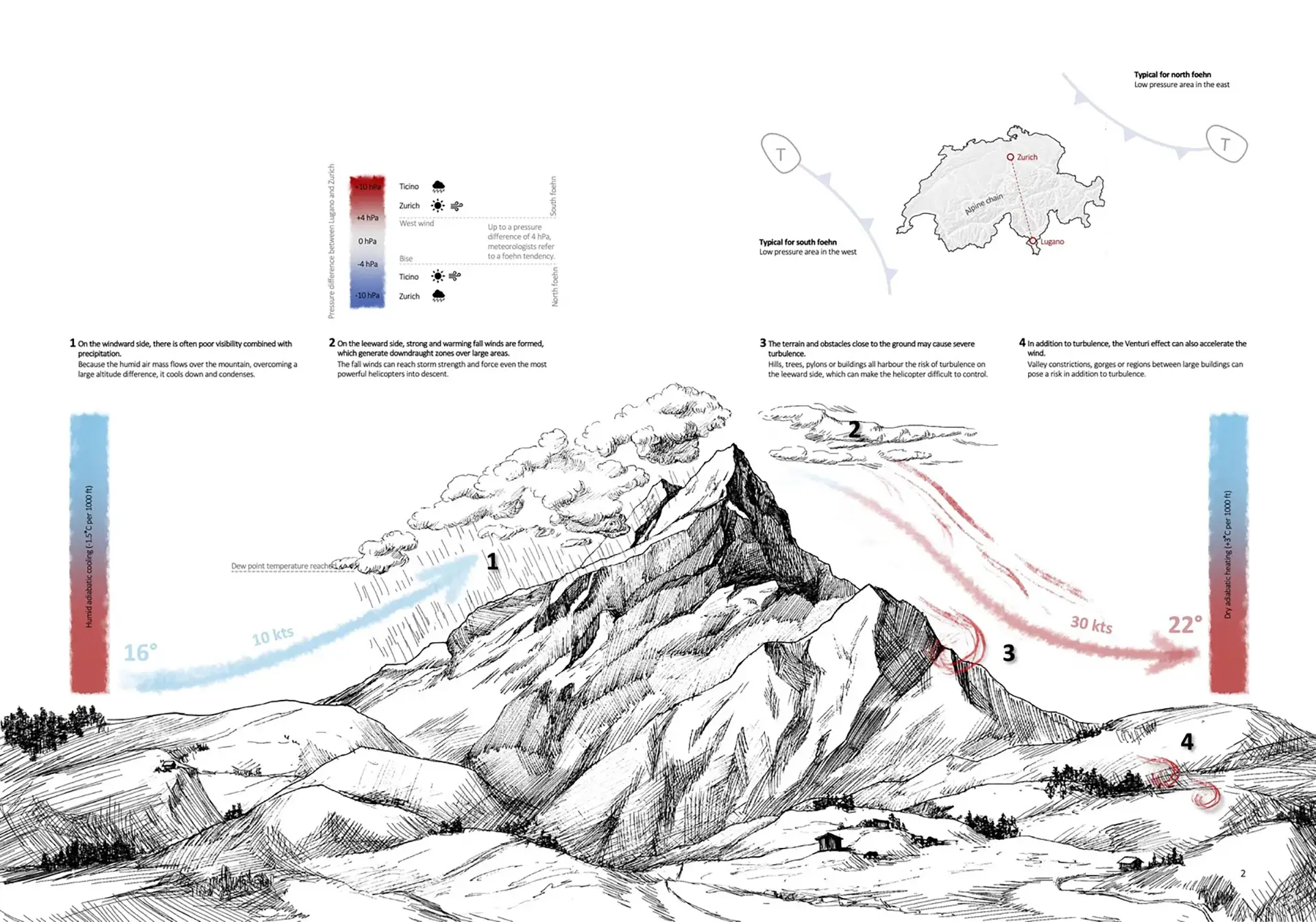

The weather is the great variable. You can study forecasts, METARs, models, and still find yourself in conditions that don’t match any of them. The mountains make their own weather, and they do it faster than you might think. The mistake many pilots make is treating weather as the enemy, something to be fought through. That mindset burns you. The trick is to work with it, to understand its patterns and accept its limits.

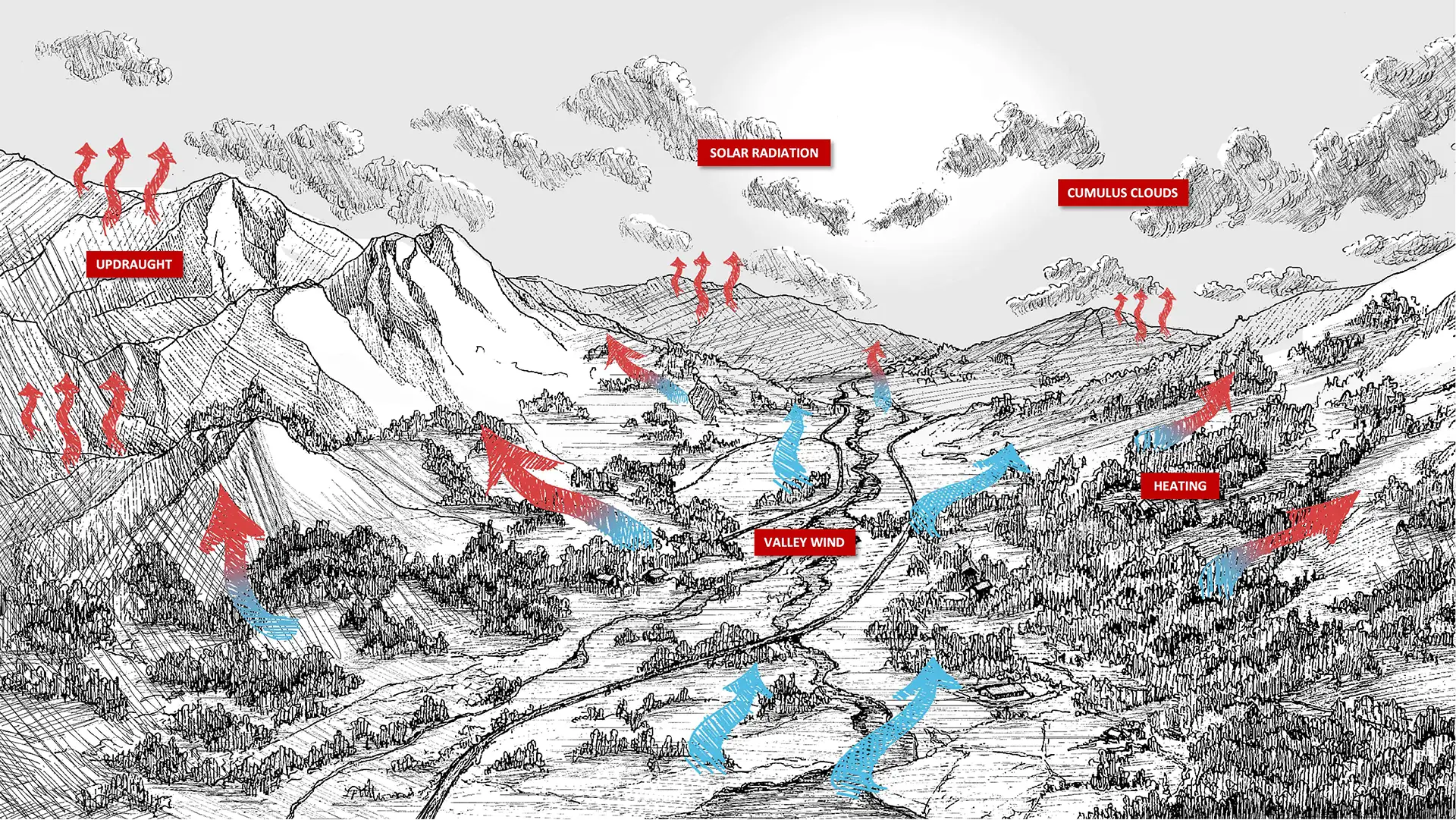

Mountains don’t produce random surprises. They produce signatures. Katabatic winds drain off glaciers in the morning. Thermals punching up the slopes by noon. Clouds wrap around passes in the afternoon. If you’ve flown long enough, you start to see the rhythm. And once you see it, you can play along, even exploit it, instead of pushing against it. I’ve had flights where the valley ahead looked wide open, only to find it choking on fog minutes later. Or glacier approaches where you had blue sky when you landed, and a whiteout when you were ready to lift again. You don’t “beat” that kind of weather. You respect it, adapt to it, or you wait it out.

Sometimes the best tactic is to turn back early. At other times, it’s riding the ridge lift on the updraughting side like a glider pilot

using a thermal instead of wrestling turbulence in the lee. It can also mean choosing an alternative route when the first one is blocked.

And every now and then, it’s simply patience; mentally putting the kettle on and waiting until the system has passed.

Pilots who carry that mindset don’t look braver; they look calmer. They’ve stopped trying to wrestle the weather and started letting it set the terms. That doesn’t mean giving up or turning back at the first cloud on the horizon. It means flying smart enough to stay alive, and strong enough to be back in the air tomorrow.

In the end, no chart or forecast replaces curiosity. The pilots who truly understand mountain weather are the ones who keep asking why? Why do the wind bends here, why the clouds form there, why the valley clears at one hour and closes the next? Hangar talks, local stories, shared experience; they all feed that habit of questioning. Over time, the rhythm of the mountains reveals itself, not in textbooks, but in the patient eyes and curious minds of those who keep paying attention and keep learning.

Plan B – Keeping Options Alive

Performance and weather are the big external factors. Plan B is the internal discipline. The thing that makes sure that when the first option collapses, you’re not trapped.

Most accidents I’ve read about or heard of follow the same storyline: the crew pressed on just a little too long. They thought the weather might improve, the valley might open, the power might stretch just enough. By the time it didn’t, there was no exit left. In mountain flying, outcomes aren’t always a straight reflection of good or bad decisions, or even good or bad intent. Both can lead to safe endings, or to close calls. What makes a difference is how much risk the pilot manages to take off the table. Having a Plan B ready before it’s needed doesn’t guarantee success, but it gives you room to adapt when things shift. And that room often decides whether a situation stays manageable or slips into the accident report pages.

That can be as simple as identifying alternate landing spots on the way in. Or briefing an escape route as seriously as you brief the approach. Or telling yourself before take-off: if the numbers don’t add up when I get there, I already know where I’m turning instead. It’s not about pessimism. It’s about buying peace of mind, and often, time. Flying without a fallback builds pressure. You start seeing only one path forward, and when it closes, you’re trapped. Flying with a Plan B keeps you clear-headed. You can actually make the decision to abort, because you’ve already rehearsed it in your head.

I often say it out loud before lifting: “If this doesn’t work, where do we go? If the pass is closed, what’s the turnaround? If the LZ isn’t safe, what’s the alternate?” With time, those questions become second nature. And when you share them with your crew, and sometimes even with your passengers, everyone ends up in the same bucket. They carry the weight of that decision-making ladder with you. It creates a shared awareness, a quiet understanding that these flights are not carried by the pilot alone, but by the collective attentiveness of everyone on board.

A Plan B doesn’t just give you another option. It gives you the confidence to fly knowing that surprises don’t have to end in desperation. That’s worth as much as any chart or forecast.

Wrapping It Up

Mountain flying isn’t about heroics. It’s not about “taming” the terrain or forcing missions through. It’s about performance you can trust, weather you respect, and robust fallback options you actually plan. There are plenty of other elements: crew coordination, decision-making, navigation, fuel management, considering elements from a flight tactics perspective, and survival skills. But if you carry these three in your mental toolkit: performance, weather, and a solid Plan B, you’ve already tilted the odds in your favor. They won’t make you invincible, but they help keep the balance leaning your way when the mountains start asking hard questions.

None of us has unlimited chances to learn every lesson firsthand. The only way to make progress is to share; openly, honestly, without ego. From one pilot to another.

Because at the end of the day, the mountains will always be bigger, stronger, and indifferent to our plans. The best we can do is fly them with the humility they deserve, and with the discipline that keeps us, and the people we carry, alive.

Mountain flying isn’t an add-on. It’s a discipline, and when we share knowledge openly, we make those invisible lines visible to each other.

Simon Wittinger began his aviation journey two decades ago as a paraglider pilot before transitioning to helicopters, where he has built a career spanning diverse environments and missions. He is now a helicopter pilot, instructor, examiner, and author with operational experience in the Swiss Alps, Greenland, and the coastal mountains of British Columbia.

His career has included mountain flight instruction, utility flying, medevac, and other commercial operations in demanding terrain. Alongside his operational work, he has developed a structured approach to mountain flying training and authored the Mountain Flying Handbook, a resource aimed at improving knowledge and decision-making for pilots worldwide.

HOME

HOME