One of the true privileges of my role as the Vice Chair of the Vertical Flight Society's Operations and Infrastructure Committee is to read the large number of Technical Papers presented to the Society for consideration every year in the weeks running up to the Society's annual Forum. As a reptile-brained aviator with a history degree, my intelligence is routinely challenged (and often exceeded...) by the depth of the scientific and technical knowledge presented. This year was no exception. The 'Ops & Infra' committee has a broad remit, including eVTOL, Airborne Firefighting, military operations, uncrewed operations and all of the supporting infrastructure, such as Vertiport designs and Heli Decks. We reviewed papers presenting highly technical proposals in support of all of the above and were fortunate to have several of the authors join us at Forum 81 in Virginia Beach to present their papers to the committee and assembled VFS members.

This year, our highest graded paper and presentation was from Lincoln Laboratory, a U.S. federally funded research and development centre associated with Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and the German Aerospace Center (DLR). Co-Authored by Margarete Groll (MITLL), Dr Phil Stepanian (MITLL), and Dr Isabel Metz (DLR), the Paper was entitled 'Wildlife Strike Mitigation in Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) - Key Technology Gaps & Proposed Solutions' and the committee were delighted that Maggie Groll was able to join us and deliver a most accomplished presentation.

That Maggie's presentation skills were so finely honed came as little surprise. In a 'previous life', Maggie was a US Navy MH-60 helicopter pilot, so taking a complex subject and making it accessible to an audience is a familiar, routine, and comfortable activity for her.

While the Paper and Presentation highlight the problem space and proposed mitigation from an AAM perspective, it is patent that Wildlife

Strike is a historic and current problem for all vertical lift platforms, not just the new generation of eVTOL machines. In my

military flying career, I had several bird strikes while operating at low level, the worst being (I think...) a Seagull that managed to tear

one of the landing lamps completely off my CH-47 Chinook, leaving a pair of wires merrily arcing under my cockpit floor. As Maggie noted,

however, eVTOLs may well have more of a problem with wildlife/bird strikes due to their relatively small size and much quieter

propulsion/rotor systems, and it is intended that future AAM designs will be fully Autonomous, without an onboard crew maintaining

Situational Awareness (SA) or using the 'Mk1 Eyeball' to 'see and avoid' threats.

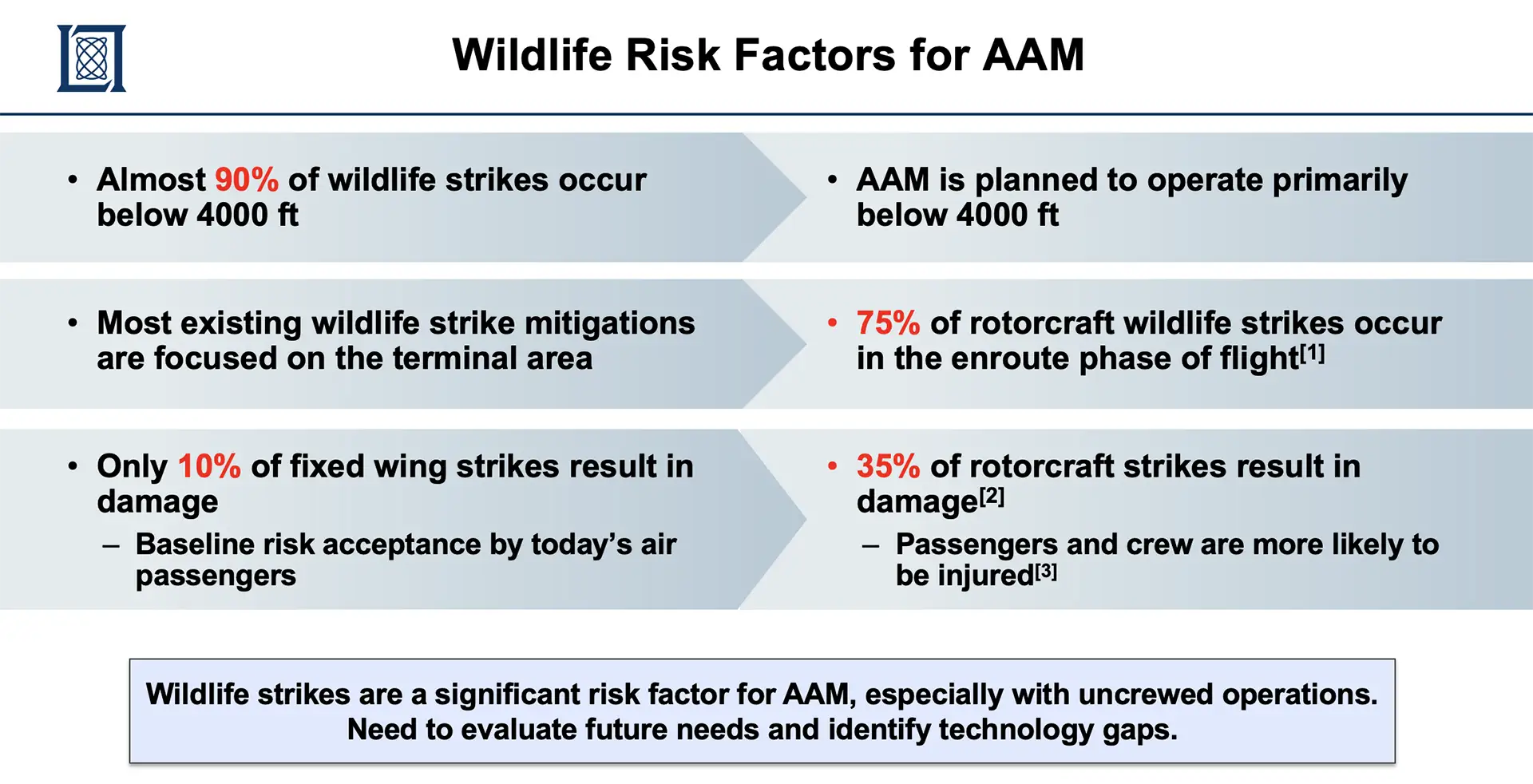

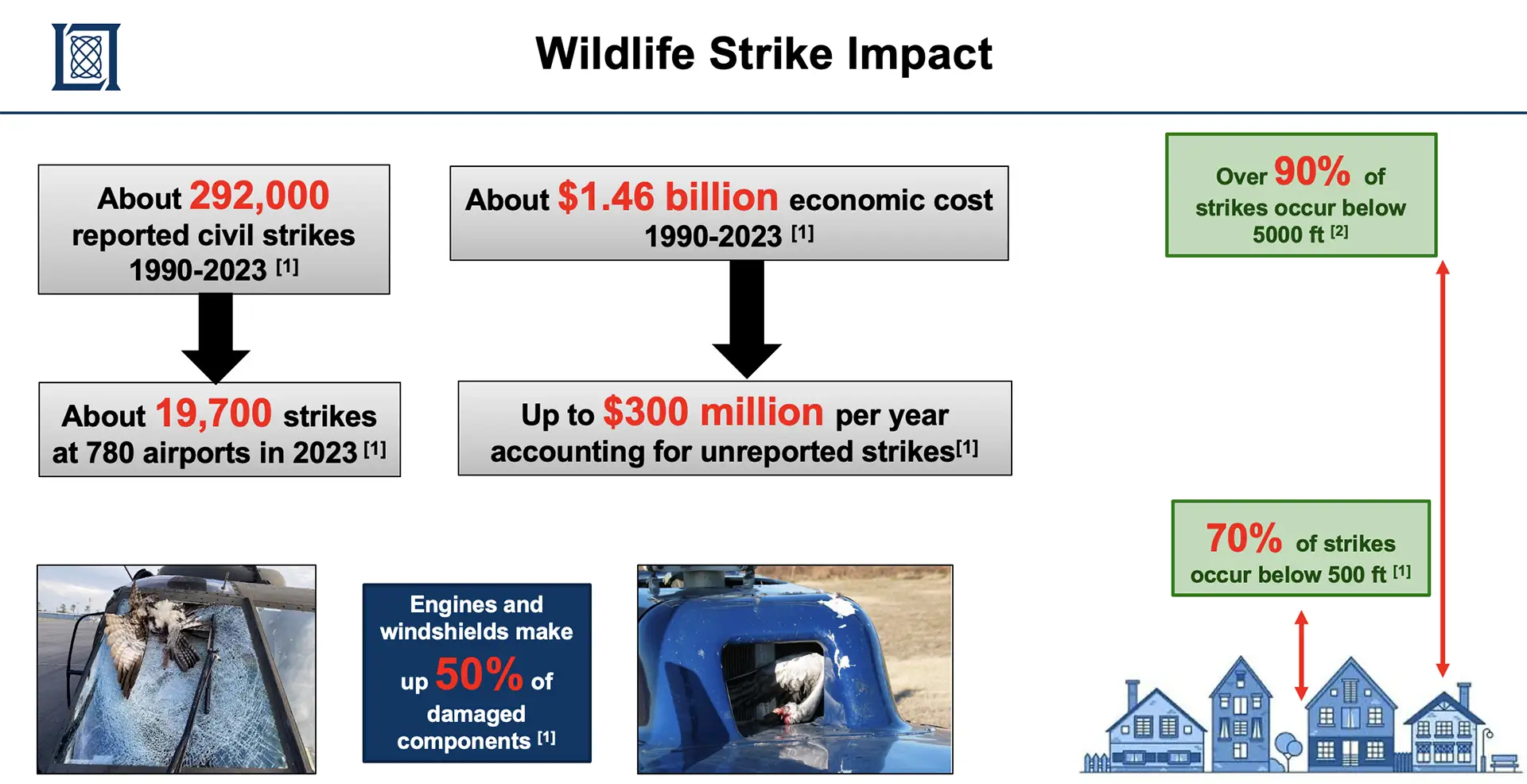

Speaking of threats, Maggie's presentation started with an assessment of the risk factors to AAM (and, by extension, helicopters). According to the research conducted by the authors, over 90% of wildlife strikes occur below 4000ft AGL, which is clearly an issue for most vertical lift platforms, but acutely for AAM, which will operate exclusively in the low-level regime, mostly below 500ft as they ply their trade in major urban centres. Of those wildlife strikes that occur, for conventional rotorcraft, some 75% happen during the en route (cruise) stage of flight - a figure I can find credible; from memory, all of my bird strikes happened in the low-level cruise between 50-100ft and at between 100-140kts; not during the take-off and landing phases. The MITLL/DLR study suggests that this is due to existing ground-based wildlife strike measures at airports and well-established heliports. Such measures can include bird patrols, using bright lights and pyrotechnics to keep birds away from operating surfaces, restricting access to food and nesting materials that can attract wildlife, and even employing trained birds of prey to provide a more natural 'incentive' for wildlife to perhaps settle elsewhere. Seasonal migration paths can be measured, and larger flocks can be detected by radar, with a warning issued. From my perspective, I also think that a rotorcraft or eVTOL is easier for wildlife to see, hear, and avoid at lower airspeed. During transitions, up or down, the aircraft tends to use a higher power setting (usually), which, in turn, results in greater blade pitch and coning angle, both of which invariably cause a distinctive, loud rotor noise as airflow separates from the main rotor.

Interestingly, the historical record also shows a marked difference between Fixed and Rotary-Wing platforms in the literal impact of a wildlife strike. For fixed-wing aircraft, only some 10% of wildlife hits result in any appreciable damage. Probably as most will hit a relatively robust part of the platform (wing leading edge, nose, windscreen, landing gear, engines). The result is a broad acceptance that the risk is tolerable for passenger operations. However, the corresponding figure for rotorcraft is some 35%, and that might have a negative impact on the willingness of the general public to get into a AAM platform.

Why?

My suggestion is that the optimisation for, and flexibility of, vertical lift operations create vulnerabilities to damage that fixed-wing platforms simply don't suffer. Although at prima facie, a rotorcraft has a similar set of attributes to a fixed-wing platform, the reality is that they are quite different. Engines, for example, have very different characteristics; in large passenger aircraft, the engines are high bypass turbofans, meaning there's a lot of 'space' and components such as fan blades are correspondingly large and strong. By contrast, helicopter engines, for packaging and size reasons, have significantly less 'pass through' and can therefore be more vulnerable. The major factor, however, is the drive towards 'added lightness' for all vertical lift aircraft. Large passenger airliners can justify the weight of sturdy landing gear and heavy windscreens due to their size and operating speeds; helicopters routinely cannot, and therefore, there is a likelihood of increased damage from wildlife impacts. Moreover, while wings do have leading-edge lift-enhancing slats, they are more damage-resistant than rotor blades and rotor heads; the latter often have a plethora of hinges, control rods, and hydraulic interfaces that are open and exposed. A bird strike at 120-140kts can cause significant damage, especially if the bird is of an appreciable size. I had a colleague hit a large bird (a Vulture) in Iraq while transiting at low altitude and high speed; the bird smashed through the windscreen and ended up still alive, just, in his lap, leaving him covered in blood, shocked, and incapable of operating for several minutes.

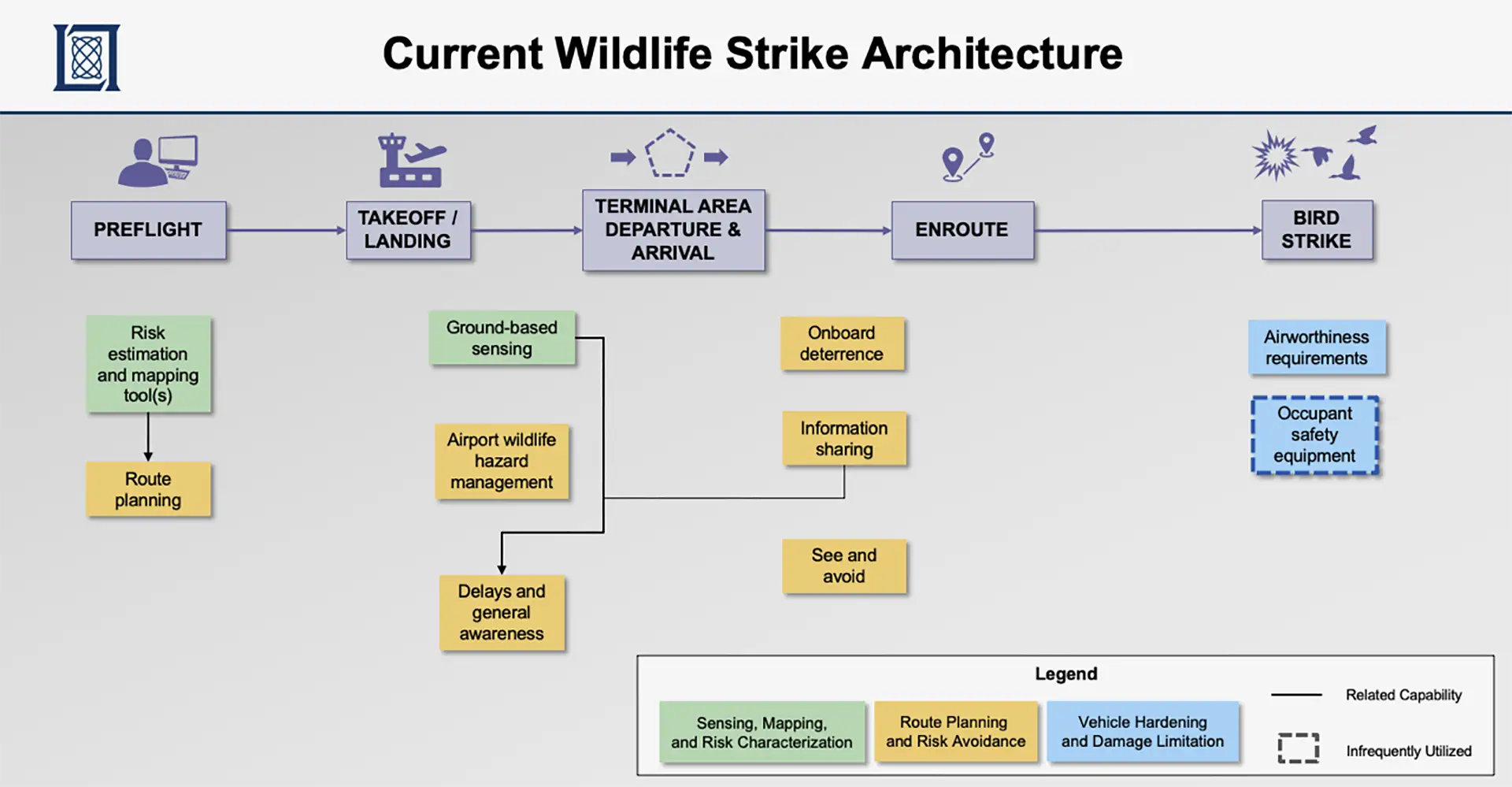

To try to avoid wildlife strikes, there are existing processes, as Maggie explained, using an exemplar 'architecture'. It starts pre-flight with using wildlife risk tools which contain a priori data on wildlife activity, enabling crews to plan their departure, arrival, and transit routing to a limited extent to minimise the risk. Active and Passive measures can be used at the airfield (or Vertiport), such as observers (including ATC) and the aforementioned bird patrols. En route, the crew can receive warnings from other operators and can use (if the tactical situation permits) bird deterrence features such as pulsing the aircraft lighting systems. However, the crew ultimately continue to rely on 'see and avoid'. The final recourse, if hit, is not to be damaged too severely, and that starts at the design stage with certification standards for component strength and airframe 'hardening'.

The need for all aspects of wildlife strike design tolerance was graphically illustrated with the loss of a USAF HH-60G Pave Hawk helicopter in the UK in January 2014. The aircraft, on a night low-level training mission flying on NVGs at approximately 100ft/110kts, transited a bird sanctuary while trying to avoid creating noise pollution by not overflying local villages as it positioned for its simulated ejectee pickup. Sadly, the crews' good intentions resulted in a large number of Geese being startled into flight, and the HH-60G was struck by several birds in the 6-12lb (3-6 Kg) weight category, creating impact energies well in excess of design and certification requirements. At least three Geese penetrated the cockpit windscreen, hitting both pilot and co-pilot and rendering them unconscious. The gunner was also struck, and another bird punched through the aircraft's nose, destroying the aircraft's Trim and Flight Path Stabilisation system, resulting in the aircraft rolling and impacting the beach some three seconds after the bird strikes, tragically killing all four crewmembers.

The main thrust of the MITLL/DLR recent work in this area, and of the paper and presentation delivered to the VFS, was to identify current

capability gaps and propose a methodology to help close them.

As with all credible studies, the team began with a literature review of over 80 existing papers, an evaluation of existing technologies, and a horizon-scanning exercise to identify technologies under development. They then completed a series of thought experiments and interviews with experts. From this work, the team could determine the quality of the technology currently in place and the mitigations implemented by the onboard crew. Coupled with an appreciation of the threat, it enabled a 'gap analysis' to be produced, especially when considering uncrewed AAM operating without the benefit of a trained pilot's lookout, but which, of course, continues to have relevance for crewed vertical lift operations of all types.

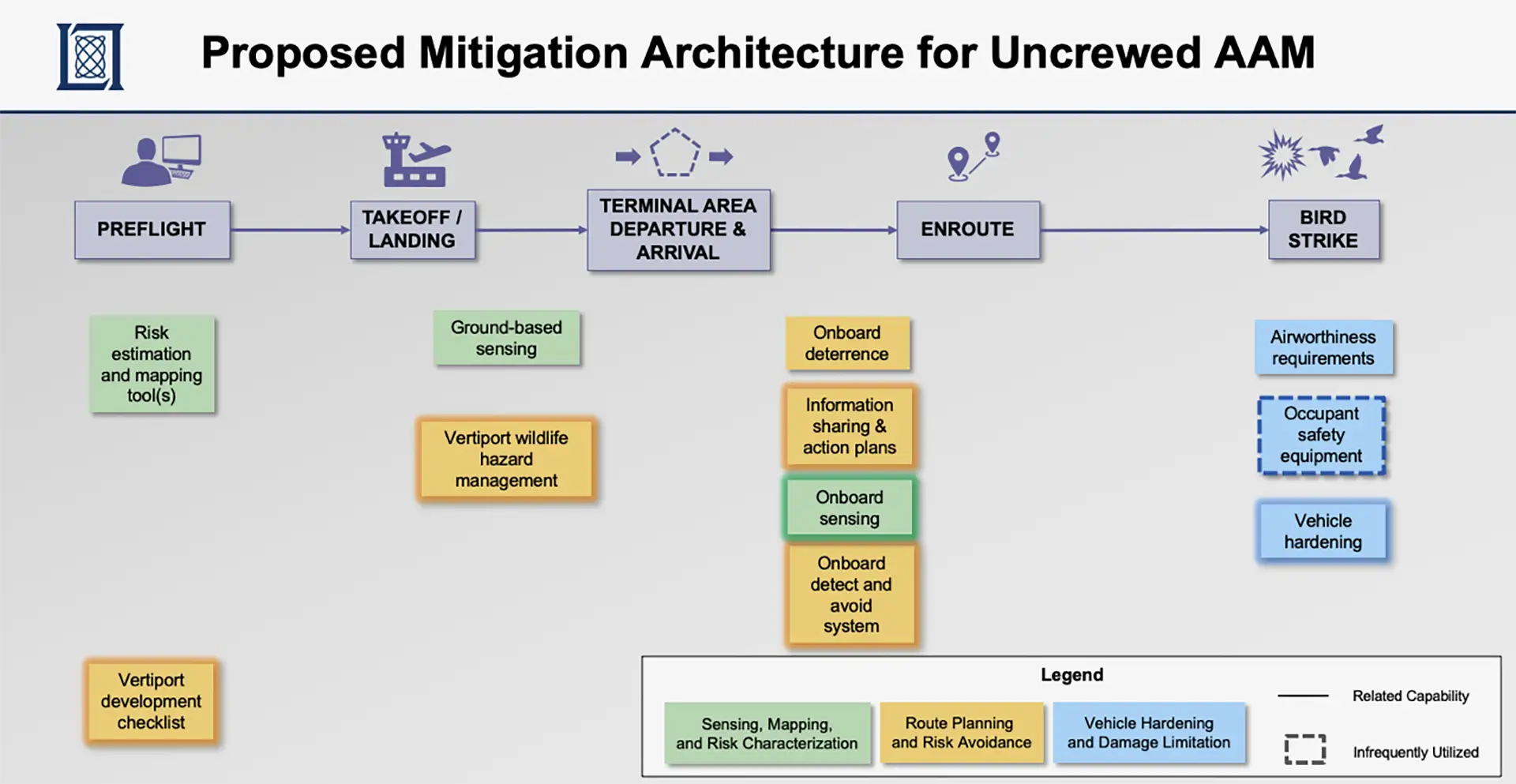

The proposed process for AAM starts with due consideration of the Vertiport location and the surrounding airspace, including corridors in and out. Where possible, sensibly, the Vertiport should not be located in proximity to areas of significant wildlife activity (such as wetlands). Opening times can also be adjusted in line with local wildlife 'habits' and adjusted seasonally due to changes in daylight hours, breeding seasons, and migration pathways. They propose creating a 'Vertiport Development Checklist' that builds on the location aspects discussed and adds practical measures, such as landscaping to discourage wildlife from settling on the Vertiport and its environs, and deploying active wildlife deterrent measures.

En route, improved information-sharing technology could allow the air vehicle to relay wildlife hazards and re-route accordingly if the risk exceeds an accepted threshold. Vehicles could also benefit from newly developed active and passive features to increase visual/aural detection by wildlife and, where practicable, mitigate wildlife risk via component redundancy and airframe hardening - accepting that these will need to be weighed very carefully, and literally, against the empty mass of the vehicle. Finally, to replace that 'see and avoid' ability provided by the pilot, uncrewed AAM will need some form of 'sense to avoid' (S2A) system. The S2A system can potentially, in my opinion, have some form of algorithm-based manoeuvre control based upon wildlife size; the impact of a small bird can probably be tolerated - it just may cause shock and distress to passengers and (through personal experience) leave nothing more than a grisly smear down the windscreen, whereas a hard manoeuvre to involve a larger hazard might be prudent. Interestingly, the team also noted that Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), such as a helmet with a visor, unequivocally provides significant mitigation in the event of a wildlife strike, though is seldom required in civilian flying. From a military perspective, when operating at low level, it was often mandatory to fly in helmets with at least a clear visor down to provide a degree of protection in the event of a penetrating wildlife strike. Our helmets were heavy, expensive, and custom-fitted to our physiology. Such an approach may prove impractical in time, cost, and weight for AAM – to say nothing of its adoption by VIPs ('helmet hair' is often not a good 'look' on arrival...) - making the case for passenger compartment 'hardening' more relevant.

MITLL/DLR also highlighted a potential for an enhanced ground-based segment in mitigating the wildlife strike risk. However, existing

weather radar has limitations in detecting birds reliably - indeed, in some cases, they are deliberately filtered out to 'clean' the

primary return when looking for aircraft. It is also impacted by clutter when employed at low level. There are other technologies now

available, especially in terms of small Electronically Scanned Arrays (ESA), that have been developed for detecting ground movements and

small UAS. The deployment of a number of ESA radars at an HLS or Vertiport could provide a much better 'picture' of the air and

ground movements of wildlife, birds and even vehicles and personnel. The 'air gap' between the ground infrastructure and the

operating picture afforded to the air vehicle also needs to be closed. The full gamut of users, air and ground, operating in and

around a vertiport/HLS need to be fully informed in real time - and the 'recognised picture' can be enhanced by air vehicles being able to

pass their sensed 'threats' to the network - especially in the anticipated high traffic density of an AAM Vertiport; the ideal is a near

real time 'all informed' network.

That 'all informed' nirvana needs to be presented to crews, remote pilots, and operating staff in a format easily interpreted by all users. Maggie noted that, perhaps, an application similar in approach to the likes of 'Waze' could be developed that has the AAM standard routes installed, is aware of the location of AAM-networked vehicles (helping with maintaining separation) and other aircraft in the vicinity, and can flag up, as an alert, any reports or detection of wildlife hazards.

In terms of 'onboard deterrence', Maggie briefed that the current lighting / acoustic systems work up to a point but are largely 'one size fits all' in approach. Work is, however, underway to develop species-targeted deterrents. This work is looking to better understand the differences in perception between species and, critically, should be imperceptible to humans to avoid unwelcome distraction for operating crews and Vertiport staff, and also to prevent any long-term health damage (such as hearing loss for example) to crews, staff, passengers, and local residents.

Improving onboard S2A, especially for autonomous AAM, will be crucial to safe operations where there is a residual risk of wildlife strike that cannot be mitigated by terminal area technology and procedures, or, indeed, during those higher risk transit phases of flight. S2A technology has a number of challenges. I've participated in a number of S2A development programs and flight trials that have attempted to identify and mature technologies to detect other aircraft to mitigate the risk of Mid Air Collision (MAC) for both crewed and autonomous platforms. It's tough; the airborne environment is ever changing, with light, contrast, shadow, and clouds all providing 'clutter' that increases the risk of false declarations - and a system constantly 'crying wolf' rapidly becomes ignored. Conversely, if the algorithm is 'tuned' to reduce false alarms, the Percentage Declaration (PDec) often reduces commensurately. The solution is often found in having at least two complementary systems that can be blended or fused to deliver an output – i.e., a thermal and optoelectronic camera system operating alongside a small ESA radar. With such a system and a 'threat library' featuring the anticipated wildlife hazards expected to be found in the operating area, a pragmatic balance between focusing on detecting threats that could damage the air vehicle and those that just 'smear glass' or 'scrape paint' is possible. Sensing and avoiding wildlife threats that could pose a genuine risk to the platform and its passengers is, to me, a sensible option. The final arbiter is, of course, the relationship between the time to impact and the air vehicle's ability to effect a safe manoeuvre to avoid impact. The S2A system needs to detect and declare those damaging threats in enough time for the pilot, or autopilot, to understand the collision geometry, input a control input, and then see it take effect. In MAC terms, such a manoeuvre is easier as another manned platform or UAS will (usually) operate predictably and in line with the standard 'Rules of the Air'. No such guarantees apply to wildlife...

The final aspect that Maggie briefed is how to harden the air vehicle to better survive a wildlife strike. For vertical lift, ever conscious of unladen mass and its impact upon revenue generation, there is only so much hardening that can be provided. The task is to identify those vulnerable aspects of the vehicle that can be reinforced - such as flight control systems and rotor blades, or indeed the human pilot if there is one. Expecting passengers on an air taxi to use PPE may well be a step too far, however. The other factor that Maggie noted was that many of the proposed AAM designs have a multi-rotor configuration and resilience to damage on one or more rotors or distributed power units needs to be considered in terms of performance and control.

The risk from wildlife strike remains a potent threat to flight safety. With the new generation of AAM vehicles and associated infrastructure, there is an opportunity to look afresh at this ongoing issue. Importantly, the broader aviation community should look very carefully at developments in this area, and where there is best practice in terms of operating process and technical solutions, consider adopting it. The technology, in particular, may well prove to be useful in helping to reduce the MAC risk with other crewed and uncrewed air users.

HOME

HOME