In July 2023, the Australian Army suffered the loss of an MRH90 helicopter in the waters of the Great Barrier Reef in Queensland, Australia. Mark Ogden, Antares’ editor and an experienced aviation accident investigator and military helicopter flight instructor, reviews in this two-part series, the accident report produced by the Australian DFSB. Are there lessons for military aviation in general or was this a unique event?

Please note that charts and figures used in this story were derived from the official DFSB Report

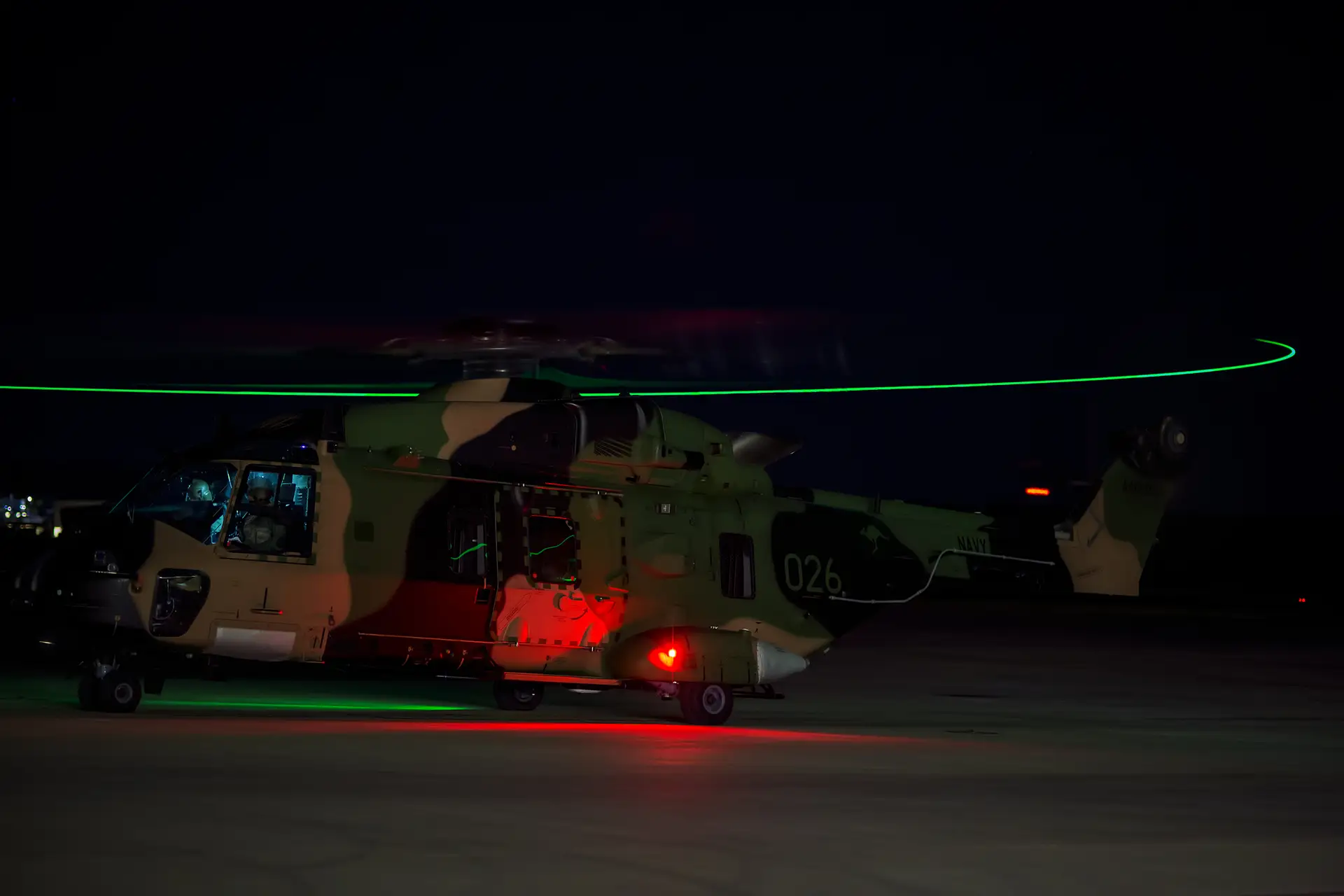

The Australian Army suffered a fatal MRH-90 accident in July 2023. Operating in formation, low level, over water, and on night vision devices, the number 3 aircraft in the formation impacted the water, fatally injuring the four crew. Following this accident, the MRH-90 was withdrawn from service and two investigations initiated. One, an accident investigation was conducted by the Defence Flight Safety Bureau (DFSB). That report is reviewed here. The second, by the IGADF (Inspector General of Australian Defence Force), is still underway at the time of writing.

The DFSB report concluded that the accident was the result of spatial disorientation leading to controlled flight into terrain. Obviously, there is much more to the story and numerous factors that contributed to the final result.

Before analyzing the report and the accident itself, it is useful to review the chequered and controversial career the MRH-90 had in Australian Army service. It provides context for understanding the Australian Government’s actions soon after the accident (removing the helicopter from service) and how these actions were not reflective of any technical or contractual shortcomings of the MRH-90or the program.

Australia’s DFSB issued its report in March 2025. Comprehensive and revealing, the report should be read and digested by all military aviators and military commands – there are lessons for everyone.

MRH90 “Taipan”

The MRH90 “Taipan” is the Australian variant of the NHIndustries NH90. It was intended to, and did, replace the Australian Army's S-70A-9 Black Hawks and the Royal Australian Navy's Sea Kings. Designed as a medium-lift, twin-engine, multi-role military helicopter, the Australian Government signed contracts for 46 of the aircraft in June 2005 under Project AIR 9000 Phases 2, 4 & 6.

The first MRH90 was delivered to the Australian Defence Force (ADF) in December 2007, and its introduction was troubled with the program being added to the Australian Government’s Projects of Concern list just four years later in November 2011, due to multiple, persistent problems that included:

Technical Deficiencies

- Critical issues with the cargo/side doors, which proved too narrow for rapid troop egress with full combat gear, compromising safety and tactical use.

- Trouble with the fast-roping and rappelling system, essential for special forces and boarding operations.

- Inadequate cabin heating and ventilation, especially for medical evacuation roles.

Poor Availability & Reliability

- Fleet availability was often well below the required operational readiness, with aircraft spending long periods grounded due to maintenance or awaiting spare parts.

- Sustaining spare parts and maintenance support proved challenging, partly because of the aircraft’s European supply chain.

Cost & Schedule Blowouts

- The program faced significant delays in achieving Full Operational Capability (FOC), which was originally planned for 2014 but slipped by years.

- Costs grew well beyond initial projections, driven by redesigns, retrofits, and ongoing troubleshooting.

In Australian defense procurement, a Project of Concern is an official designation by the Australian Department of Defence for projects suffering serious issues with cost, schedule, or performance. It signals the need for urgent remediation, often with ministerial oversight. The Project of Concern status required the Department of Defence, Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO), and the prime contractor (NHIndustries/Airbus) to develop formal remediation plans; however, ongoing reviews found that resolving the issues would require extensive redesigns and significant investment. Despite some improvements, the MRH-90 reportedly never fully met the Australian Army’s expectations. Problems persisted, and high-profile incidents (including safety concerns), such as an uncontained engine failure just four months before, continued to erode confidence in the aircraft.

In 2021, Australia had reportedly sunk acquisition costs of around AUD $3.7 billion and the Australian Defence Force estimated MRH-90 sustainment costs at around AUD $50,000 per flying hour[1], including parts, maintenance, support contracts, and logistics. In the 2020/21 financial year, the MRH-90 fleet only achieved 60.8% of its planned flying rate of effort. Annual sustainment costs for the MRH-90 fleet were estimated at over AUD $300 million per year; a figure that grew with age as reliability declined. The Australian government cited that the UH-60M Black Hawk costs would be less than half the MRH90’s cost while achieving greater fleet availability.

In December 2021, the Australian Government elected to replace the MRH-90 fleet with up to 40 UH-60M Black Hawks and 12 MH-60R Seahawks from the United States (increasing the RAN fleet to some 36 Seahawk aircraft – the RAN had by this time developed a long history in successfully operating the Sikorsky product), citing the need for more reliable and cost-effective platforms.

At the time of this accident, the Royal Australian Navy had ceased flying the MRH-90 as it transitioned the role to the MH-60R.

Come February 2024, the MRH-90 was retired from service (before its planned withdrawal date of the following December), before any planned return to flying operations. Even then, the aircraft was never far from controversy when the Australian Labor Government chose not to make them available to Ukraine in its battle with Russia. The aircraft, instead, were broken down to sell as spares, and the fuselages reportedly buried.

The Accident

The publicly available report into the MRH-90 accident, is detailed, amassing some 200+ pages and another 150+ pages for enclosures. It is worth a deep read but there is, in my opinion, some significant gaps in the investigation (maybe they were considered and appear in classified documentation but certain considerations, what I regard as missing information, do not appear in the public report) – something I will address as we step through the report. To understand how things developed, it is important to look at the history of the flight.

History of Flight

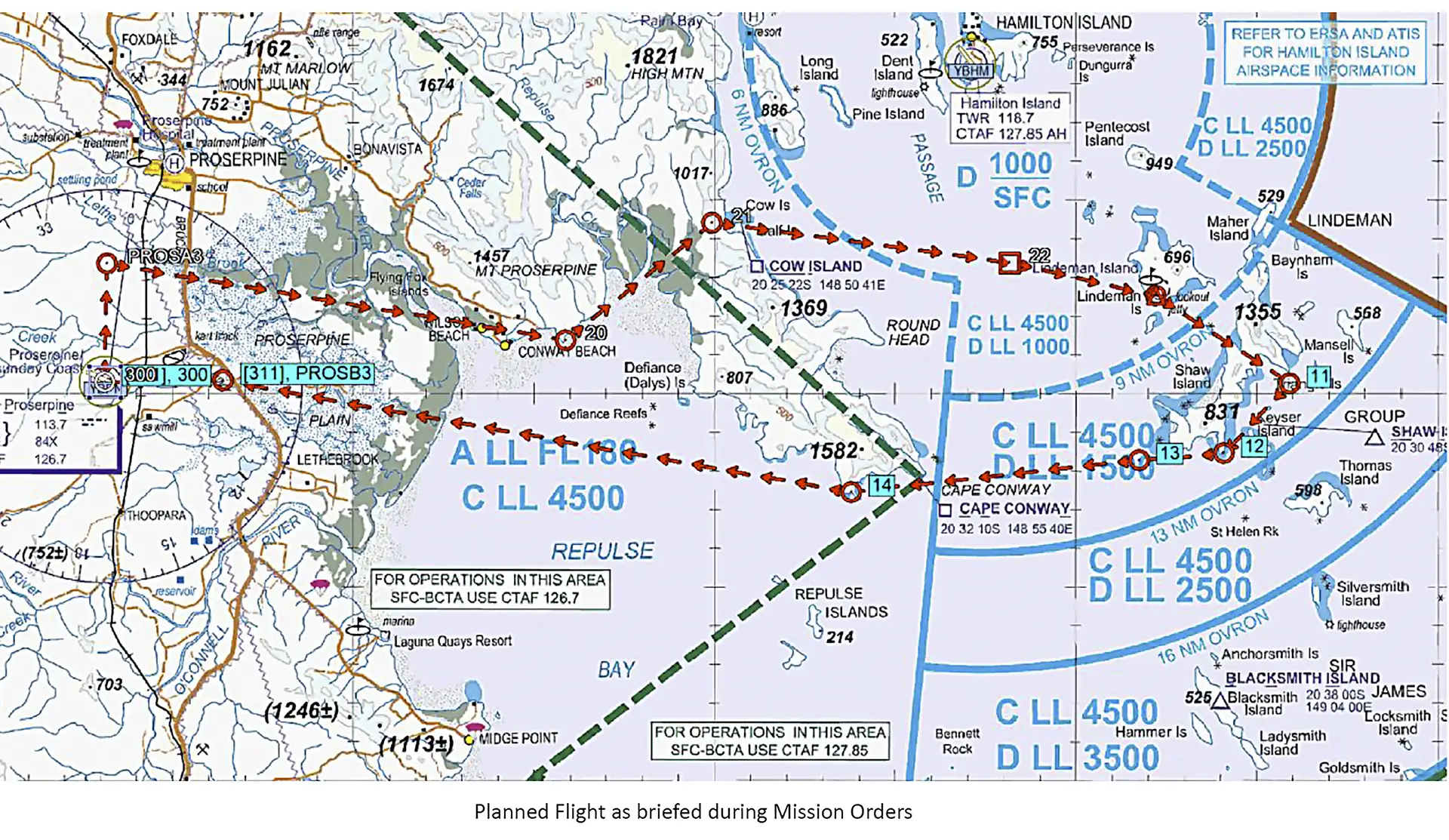

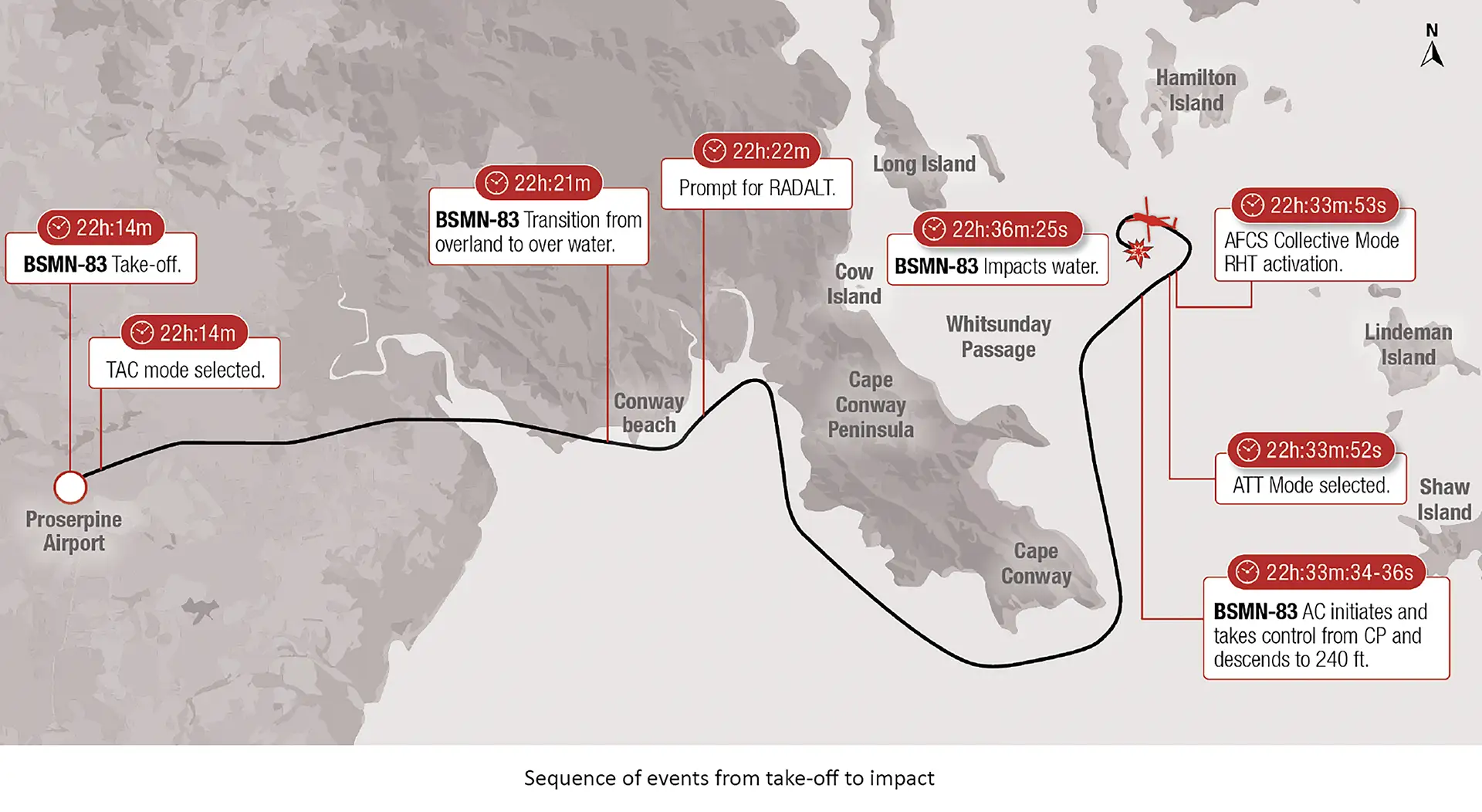

On the night of 28 July 2023, a formation of four MRH-90 helicopters (Callsigns “Bushman” 81,82,83 and 84) was tasked to conduct a night extraction of ground force elements from Lindeman Island as part of Exercise Talisman Sabre 23. Bushman 83, the accident aircraft, was the third aircraft in the formation. The crews commenced duty at 13:00 local time, received mission orders at 14:10 and conducted a Rehearsal of Concept (ROC). A ROC is a ‘walkthrough’ of the mission which, according to the report, is often used as an additional risk control to identify and brief contingency plans. B83 (Bushman 83) started engines at 21:14, and at 22:14, the B83 departed Proserpine as number three in a heavy left formation.

Seven minutes later, the formation was ‘feet wet’, entering the Whitsunday Passage. Low cloud caused the formation lead to turn right to track coastal over water. At 22:33, the Aircraft Captain (AC) of B83 took over from the co-pilot (CP) as the aircraft drifted high from the formation, and the AC reestablished the aircraft’s formation position at a height of about 240ft. At 22:34, the formation entered a left holding pattern, the first of two left turns.

Two minutes later, at 22:36:06, the lead aircraft rolled out of the left turn onto the outbound leg of the pattern, maintaining 214ft and 81kts Indicated Air Speed (IAS). Before B83 completed its turn, the aircraft accelerated in the climb from 76kts. At 22:36:19 (13 seconds after the rollout commencement) B83 was at an altitude of 356ft and 111kts when it then suddenly pitched nose down. The Voice Flight Data Recorder (VFDR) recorded multiple pitch and roll inputs. At 22:36:22, B84 (#4 in the formation) transmitted, “83 pull up, pull up, pull up”. At 22:36:25 B83 impacted the water. The total time from commencing the rollout to water impact was just 19 seconds. All four crewmembers of B83 were fatally injured and the aircraft destroyed.

Qualified, Competent and Current

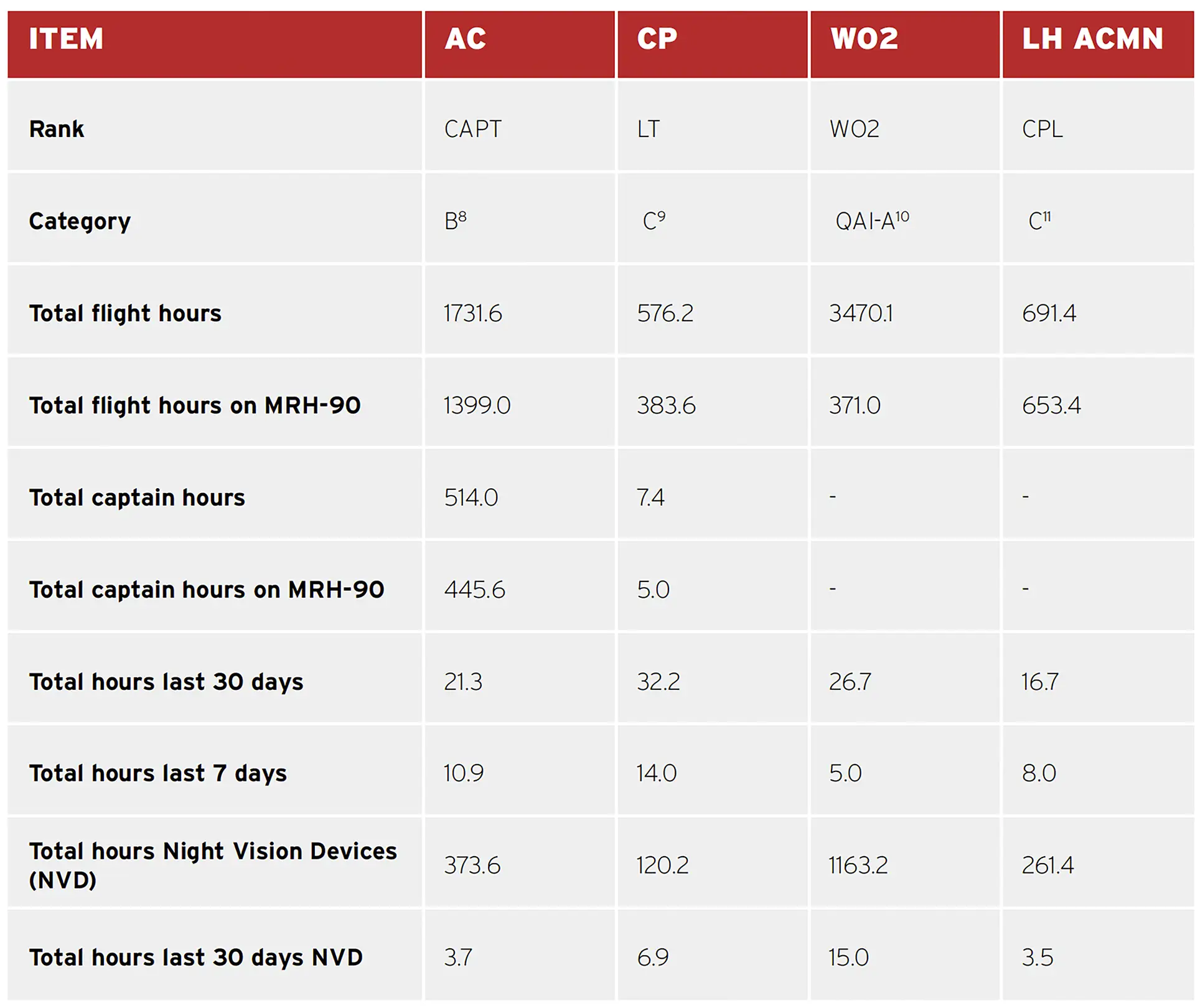

The report provided a summary of the crews’ experience with the AC having nearly 1400hrs total air experience, 514hrs as an aircraft captain and just over 370hrs total experience on Night Vision Devices (NVDs). He had flown 3.7hrs on NVD in the previous 30 days. The CP had just 384hrs total air experience, 120hrs on NVD and nearly 7hrs on NVD during the previous 7 days. Both pilots were NVD ‘current’.

Interestingly, the report notes that the crew were “qualified, competent and current: to perform the mission but the report does not explore the crew’s workup to the task. Operating low level, over water, in formation, on NVD could only be described as a high workload environment and all involved should been gradually and fully worked up over the previous days to conduct such a mission safely and effectively.

Accepting that the crew were ‘current’ given their NVD time, I’m not sure that necessarily makes a crew competent for a particular mission. For example, questions arise concerning how many times they had flown this mission profile in the previous 7 days. How many times had they flown NVD in a degraded (cloudy) environment in the week, and how many times had they flown formation using NVDs low level overwater in the previous 7 days? This question about how many times they had flown the profile and how many times they had flown low-level overwater NVD formation in the previous days would have provided the reader with an understanding of how ‘competent’ the crew was to do the mission. I’m not saying the investigators did not examine this aspect; it just does not appear in the report, and so the questions arise.

Interestingly, the DFSB report examined selected previous accidents such as the navy’s loss of a MH-60R in 2021 due loss of situational awareness on late finals to a ship and an Army 2020 occurrence involving inter-formation loss of separation while using NVD [Night Vision Devices] but does not include consideration of any potential similarities to the 1996 midair collision of Black Hawk helicopters – also at night and using NVDs. The 1996 Black Hawk fatal midair collision Board of Inquiry (BOI) report specifically highlighted that the workup training was found to be deficient. In that report, the Board found no evidence of a general lack of proficiency but did find “… a lack of mission proficiency in specific aspects”. Conversely, the Black Hawk accident BOI report did not address the role that fatigue did or did not play. It is fair to say that investigations and their associated reports continue to evolve.

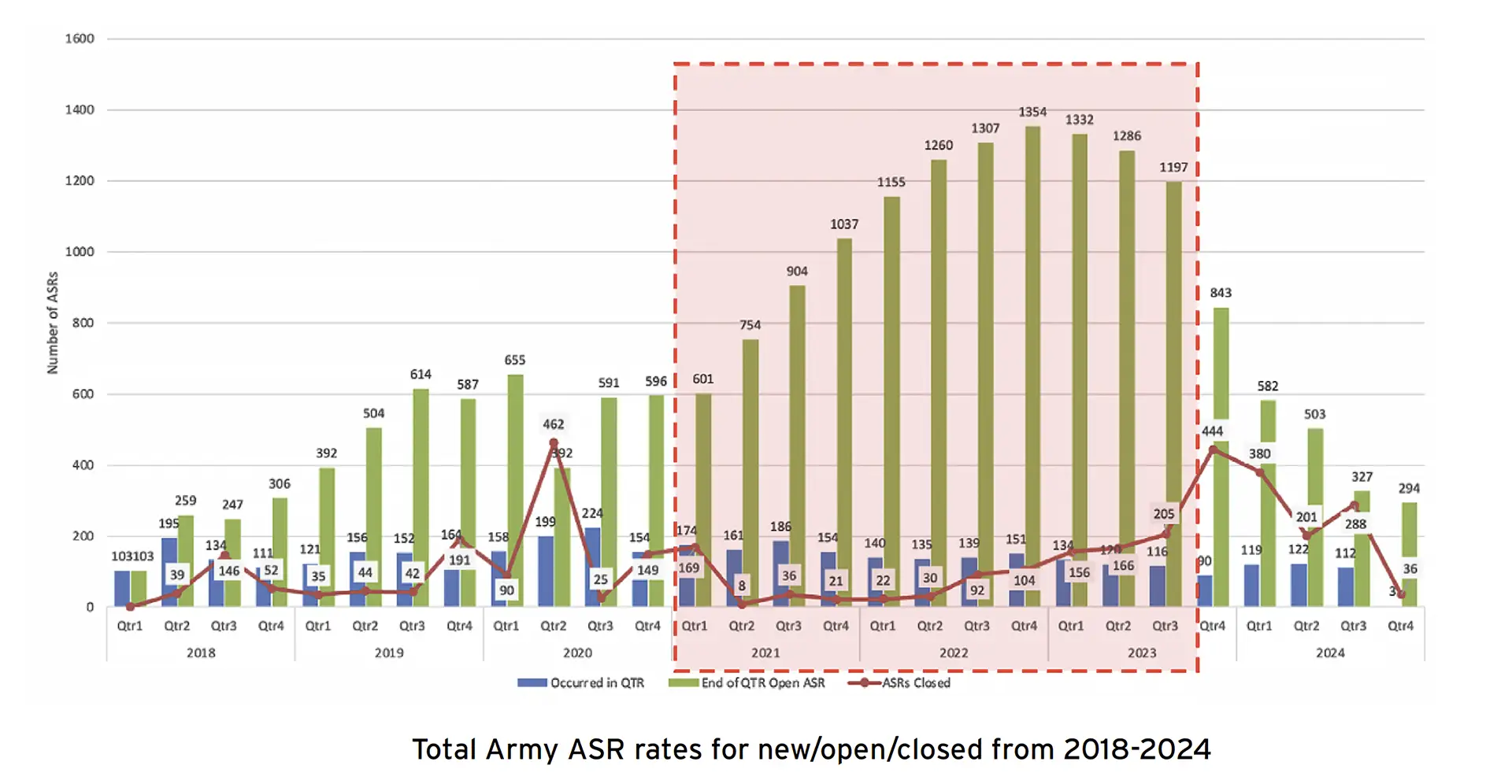

The Taipan report highlighted that multiple aviation safety reports directly related to spatial disorientation were contained within the Australian Defence reporting system. Although Class A and B occurrences were listed, there was no overall analysis of what these reports may have indicated. The report noted ‘common themes’ but no analysis or rates were provided within this report. Were there precursor markers to the risks involved? The report even noted, “…with the majority specific to rotary wing operations. Many of those were related to NVIS [Night Vision Imaging Systems] operations, and many also were during formation operations.” - but then there appeared no further analysis of what those reports may have indicated, such as any trends.

The report, however, highlighted the Army's failure to properly review or close out hazard reports, noting that a key hazard management tool, biannual reviews by the Aviation Hazard Review Board, had not been conducted. AHRBs were intended to review and oversee the progress of safety-related procedures and corrective actions – a key element of any aviation Safety Management System (SMS). So, could the Army’s aviation SMS be considered effective?

Fatigue

The report examines the sleep/wake cycles of the crew and the environment in which they achieved rest. In the previous two days, the AC had been working 16 and 17-hour days, which straddled midnight, which appeared reasonable given the night missions being flown. On the day of the accident, though, the AC had only had 5 hours of sleep opportunity with the window being 02:00 to 07:00. The day before was similar. The CP had less sleep with longer duty days. He had a 20-hour day two days before and a nearly 17-hour day the day before. He had a five-hour sleep window the day before and had been awake over 15 hours at the time of the accident, although he had a seven-hour sleep window on the morning of the accident. The one question, though, that needs addressing is the ‘quality of sleep’. The investigation conducted ‘Biomathematical Fatigue Modelling’ (which was detailed in Enclosure 1 of the report). The modelling does have limitations:

- Assumption that the individual was fully rested at the beginning of the schedule

- Predicts risk probabilities for a population average rather then the specific individual

- Does not account for the impact of workload or personal/workplace stressors

- Does not consider the influence of all components of environment stresses or workload

The modelling attempted to measure the ability of the average person to perform effectively as determined by several factors including time of day, biological rhythms etc.

The modelling showed that the AC was fatigued with a performance equivalent to having .05% blood alcohol (note: this is a measure of performance – the crew did not have alcohol in their blood) with a 37% increase in reaction time and 4.5 times more likely to experience a lapse in attention. The CP was not considered to have represented a fatigue risk at the time of accident based on the modelling.

The crew, during their rest periods, were accommodated in non-airconditioned tents with stretchers for up to 18 people. The tents were located at an active civilian airport. People interviewed after the accident reported that their sleep was interrupted by the movements of other people on different schedules, aircraft movements, and environmental temperature fluctuations, with some reporting that the quality of their sleep was poor. Consequently, the CP could have been fatigued despite his modelling score showing otherwise.

As an aside, it is important to consider the impact of fatigue on piloting skill. According to various authorities, in the last two decades, it has been identified as the probable cause of 21–23% of major aviation accident investigations[2]. Fatigue significantly increases the risk of pilot disorientation, including reduced situational awareness, slowed reaction times, and impaired decision-making. Fatigue can exacerbate sensory illusions that lead to spatial disorientation, particularly in conditions with limited visual references like night or instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) and make pilots more susceptible to vestibular illusions (sensations of motion and orientation that do not correspond to actual aircraft movement). When visual references are limited, pilots rely more heavily on their vestibular and proprioceptive senses. Fatigue can impair these systems, increasing the risk of disorientation.

The report concluded that both B83’s pilots were experiencing fatigue likely to impede optimal performance and that the AC was fatigued sufficiently to constitute a risk to safety. It also noted that organizational preconditions at 173 Special Operations Air Squadron meant that aircrew experienced cumulative fatigue and burnout.

In Part 2, we further explore the various factors that were considered to have contributed to the accident.

HOME

HOME