In July 2023, the Australian Army suffered the loss of an MRH90 helicopter in the waters of the Great Barrier Reef in Queensland, Australia. Mark Ogden, Antares’ editor and an experienced aviation accident investigator and military helicopter flight instructor, reviews in this two-part series the accident report produced by the Australian Defence Flight Safety Bureau (DFSB). In Part 2, the potentially controversial aspects of the accident report are explored.

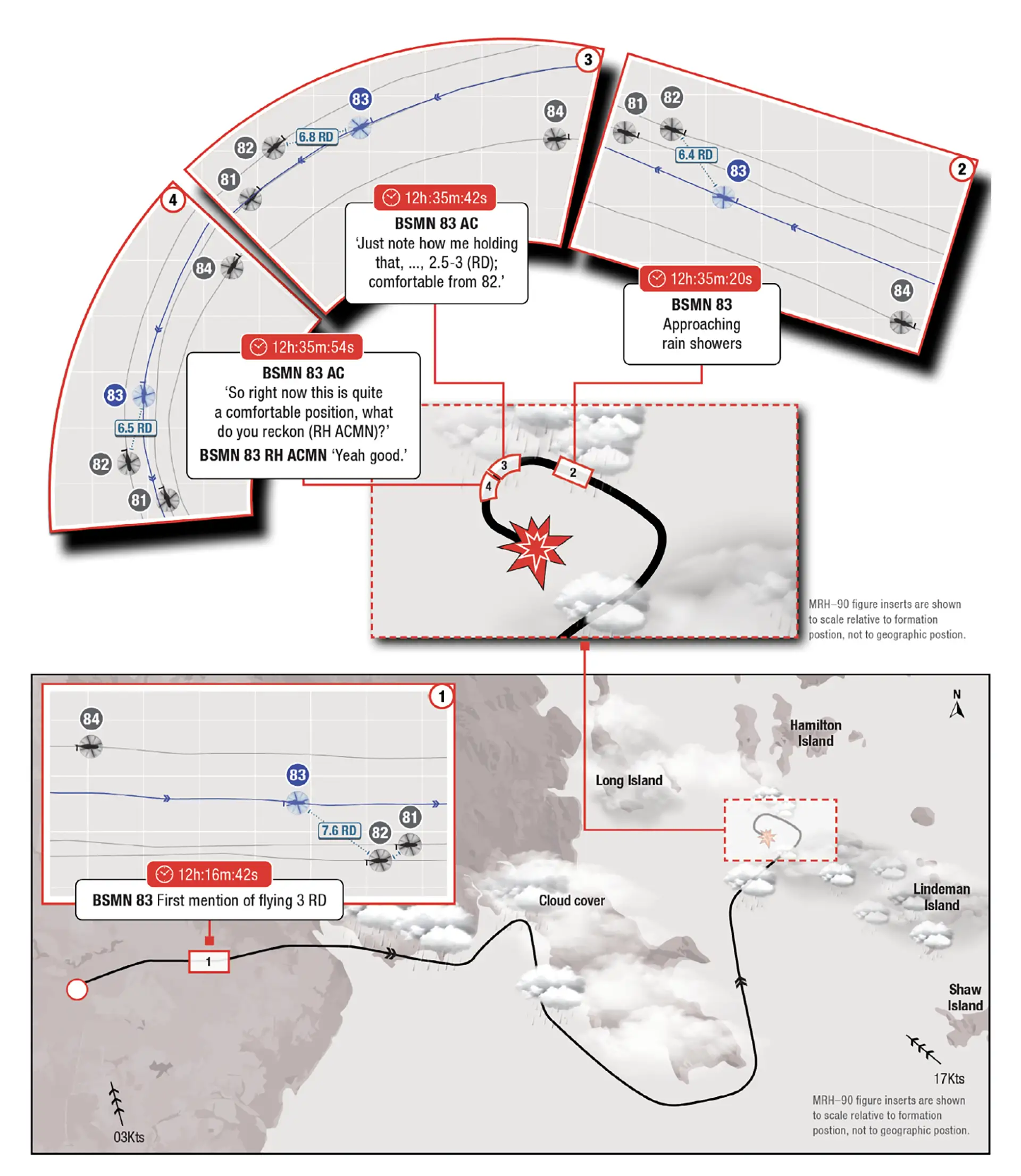

The Australian Army suffered a fatal MRH-90 accident in July 2023. Operating in formation, low level, over water, and on night vision devices, the number three in the formation impacted the water, fatally injuring the four crew. Following this accident, the MRH-90 was withdrawn from service, and two investigations were initiated (a third, it seems, was also initiated by the government’s work health and safety agency). One, an accident investigation was conducted by the DFSB. That report is reviewed here. The second, by the IGADF (Inspector General of the Australian Defence Force), is still underway at the time of writing, but transcripts of the hearings are available at https://www.igadf.gov.au/igadf-mrh-90-inquiry. The IGADF appointed the inquiry to rigorously examine the circumstances and causes of the July 2023 accident crew’s deaths to determine whether actions or inactions by ADF personnel or others, compliance or non-compliance with policies and procedures, or other matters were contributing factors.

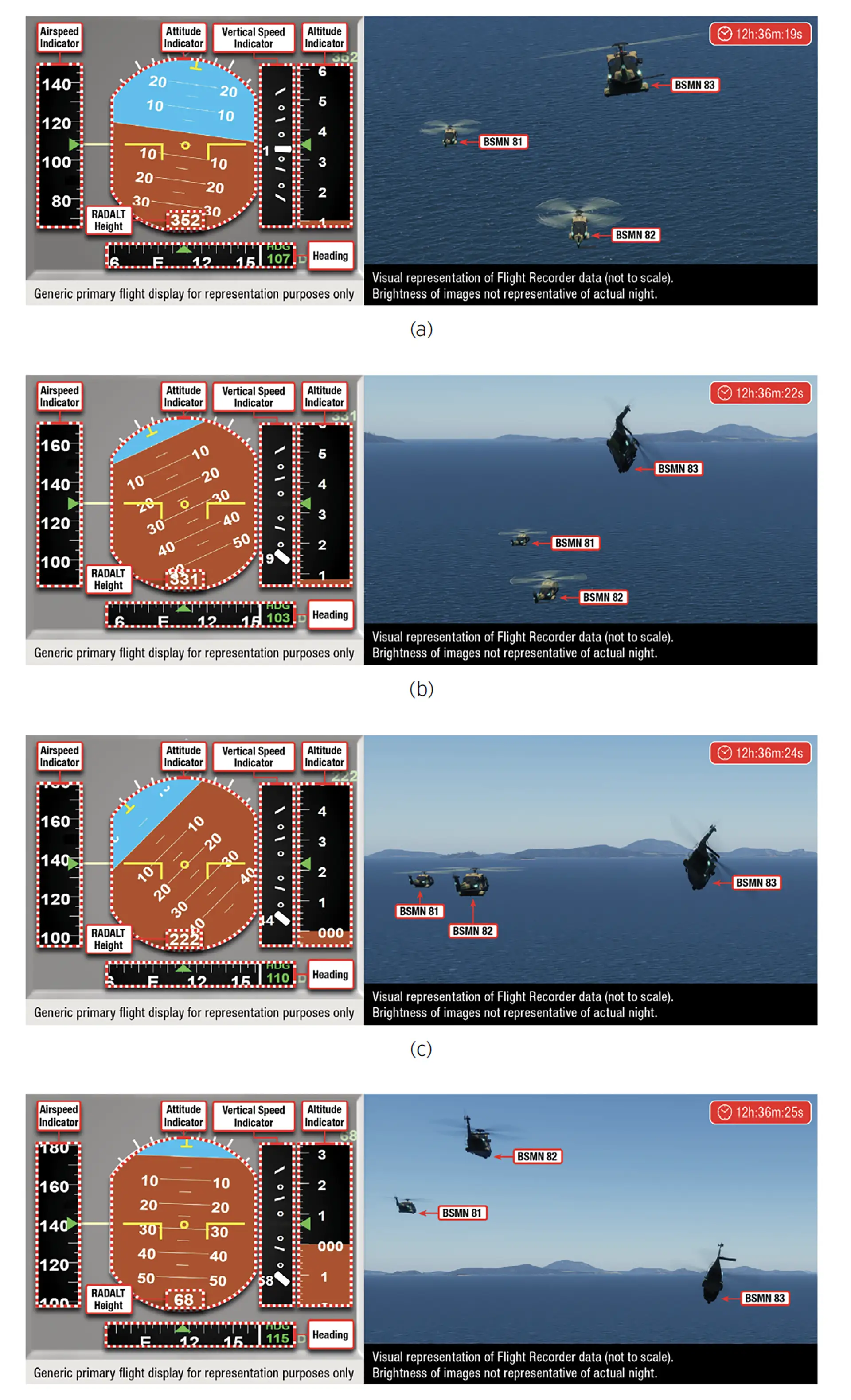

The DFSB report concluded that the accident was the result of spatial disorientation leading to controlled flight into terrain. Obviously, there is a lot more to the story and many factors that contributed to the accident.

In this part, some of the various factors that were considered to have contributed to the accident are reviewed, and how the accident report connected (or didn’t) connect the dots. The reader needs to be familiar with Part 1 of this review to ensure an understanding of the circumstances of the accident.

The DFSB stated that the purpose of the accident investigation was to:

- Determine the key accident sequence of events and the cause of the accident

- Identify any systemic and organisational factors that directly or indirectly contributed to the accident

- Make recommendations for safety system improvement in order to prevent recurrence of a similar event.

As an ex-accident investigator, my opinion is that although the report appeared to be generally comprehensive in facts presented, it fell short in its causation analysis.

The Role of Fatigue

As summarized in Part 1, the report concluded that both Bushman 83’s (B83) pilots were fatigued and that the Aircraft Captain (AC ) was fatigued sufficiently to constitute a safety risk. The biomathematical fatigue modelling appeared reasonable but while accepting the AC was probably significantly fatigued, how that materialized in his operation of the aircraft or his decision making did not appear to be robustly scrutinized made. The report stated that organizational preconditions at 173 Special Operations Air Squadron meant that aircrew experienced cumulative fatigue and burnout. Yet the report did not explore why the decision was made not to follow the requirements of the documented plan, including who made that decision and why. The flying supervision, based on the accident report, appeared overall deficient. While accepting that army aviation must sometimes operate in austere environments the risks with that requirement need to be understood and managed – particularly in peacetime. According to the report, this was not managed adequately, yet the report failed to identify how those decisions were made – they were just made, and the analysis did not appear to delve deeply into the decision-making.

Role of TopOwl

This discussion delves into what may prove to be the most controversial aspect of the investigation. There is no suggestion that TopOwl is defective. TopOwl and the software load had been accepted by the Australian Navy for its purposes and was in service with the German Army. Questions arise, however, concerning the investigation’s apparent decision not to delve into how the system was accepted into Army service or the safety of, or risk posed by, the system as it was being used on the night of the accident. Or how these decisions may have been indicative of decision-making within the Australian Army Aviation.

The TopOwl Helmet Mounted Sight and Display (HMSD) is an advanced helmet system that integrates night vision, flight data, and targeting information, then projects it onto the pilot’s visor. TopOwl aimed to improve situational awareness by enabling pilots to access critical information without needing to look down at cockpit instruments, particularly in low-visibility conditions such as nighttime operations. At the time, TopOwl displayed and integrated the image from the night vision Image Intensifying Tubes (IITs) and projected it to the pilot’s visor via a series of mirrors. Australian Army Test Pilots reported that the system lost some 50% of the visual gain in this implementation. In this case, given the degraded visual conditions (cloud, rain and overwater), little or no visual horizon was likely. The pilots were probably looking into an almost empty field of vision that had no visual information other than the helicopter upon which they were maintaining a formation position.

At 2.22, the report discussed the TopOwl/HMSD. It noted the revised symbology in the update from software 4.0 to 5.1, but the actual symbology was not provided in the public version of the report; but did note the existence of an Army Aviation Test and Evaluation Section (AATES) report that examined the Human Machine Interface (HMI) aspects of the software update. In that report, the AATES identified issues with pitch scale attitude when the pilot turned their head to either side of the aircraft.

The AATES report assessed the issue as being an unacceptable risk to flight safety. The investigation report noted that the testing was limited to two flights conducted during the day. It could, therefore, be surmised that the test pilots held serious concerns. The Australian Army’s Standards Section, however, sought to expand on the tests, not by sending them back to the assessing agency or even to another accredited testing agency (e.g. the Air Force or Navy). They chose instead to have a reassessment done by Operational Evaluation (OPEVAL), which subsequently assessed it as undesirable with recommendations for additional training. AATES reviewed the OPEVAL report and did not change its evaluation, which remained unacceptable.

Defence Aviation Safety Authority Defence Airworthiness Design Requirements Manual noted at 15.3:

Defence aircraft indicating systems must conform to standards appropriate to the functions that the instrument or display will perform. Authority recognised civil and military Airworthiness Codes prescribe design requirements that provide a sound foundation for the safe design of common Defence aircraft indicating systems (including those used as a Primary Flight Reference (PFR)). However, indicating systems that are in the early stages of technology development may be proposed for fitment to Defence aircraft to satisfy a capability need and design requirements for such systems may not have been prescribed in Authority recognised Airworthiness Codes. Consequently, applicants for an Australian MTC or MSTC must propose, for Authority approval, airworthiness design requirements based on the intended function and operation of the indicating system.[1]

Despite the test agency’s position, the Army Aviation Branch approved the upgrade, including the recommendations from the OPEVAL.

The investigation appeared not to delve into, or analyse, the efficacy of the Army’s process in this case, including decisions not to follow the required processes as detailed in the DASRs (Defence Aviation Safety Regulations) or why DASA approval had not been sought. It did note that the decision brief required a full risk analysis and the issue tracked to ensure full effectiveness of the risk control measures. The investigation found that no hazard analysis or risk assessment was documented.

Additionally, based on the information in the report, the investigation appeared to not conduct any specific modelling of what the pilot(s) would or may have perceived as regards the helmet presentation including symbology, instead saying, “Based on the information available to the ASIT, including the analysis conducted on the wreckage, VFDR and of human performance factors, the ASIT assesses that the MRH-90 Taipan HMSD V5.10 attitude information display hazard did not directly contribute to the accident.”

Yet at 2.22.9, the investigation noted that in the final 20secs of flight, B83 was in a swept echelon left position off B82 before moving to a trail position, arguing that the pilots would have been looking ahead and therefore the issue identified by the AATES would not have come into play. What the report did not note in that assessment was that the aircraft was 100ft+ above the B82 and therefore, it is conceivable that the pilot may have been looking down and to the right in looking for B82 (especially noting the yaw at the time). The speed and height deviations indicated that the pilot looking down and to the right was a potential scenario for which the HMSD indications should have been assessed and modelled.

Alternatively, if the investigation’s assessment that the HMSD did not contribute to the accident is accepted, then the question must be why there was no investigation into what factors may have led to the HMSD not providing the pilots with the situational awareness that it was supposedly designed to enhance. Did the HMSD potentially hinder the pilot’s situational awareness through an ambiguous display? If so, could the ambiguous elements have contributed to a loss of the pilot’s situational awareness? These are not statements but rather questions that remain left unanswered in the investigation.

The IGADF Inquiry transcripts revealed that there had been some consternation by the AATES at the software upgrade, the system testing and the processes involved in fielding the equipment. Yet despite being aware of the concerns held by the Army Aviation testing unit, on 29 April, 2025, the Head of the DFSB advised the IGADF Inquiry that the investigation did not investigate whether the HMSD was an appropriate system to use because “It was not within the scope of the investigation.” “The TopOwl and the system, again, was the system that was provided to Army Aviation Aircrew”. This is akin to saying that assessing the HMI (Human Machine Interface) aspects of an airliner’s flight management system should not be assessed in an airline accident.

Considering the weather conditions encountered (likely no visible horizon in passing rain showers), it is incongruous that the system designed to enhance situational awareness, which the pilots may have partially or fully relied upon, was not fully investigated and assessed for its effectiveness.

The investigation apparently failed to fully investigate through proper modelling and assessment of the system presentation in various potential scenarios. It would have been appropriate to engage other test agencies, either in Australia or in allied nations, to assist or assess the modelling. Consequently, doubt arises as to the efficacy of the report’s analysis of the HMSD’s effectiveness or contribution to the pilots’ situational awareness.

Pilot Experience/Workup

At 2.11, the report stated that the crew were “qualified, current and within crew endurance as required by …”. The formation was being flown in conditions where inadvertent instrument conditions could have been encountered. Consequently, it would be expected that the pilots were qualified, current and competent to conduct instrument flight, yet, in at least six years of operating the MRH90, the AC had only 87 hours of instrument flying time on the MRH90.

The investigation did not appear to analyze the experience and competency of the crew for the mission being conducted on the night. In effect, this was a multi-ship formation being conducted over water by NVD in marginal conditions. What was the plan if the weather went below limits and what were those limits?

There was no detail within the report of the crew’s specific flight training for this exercise. How often had the crews practised this exercise in the simulator, for example? How much training was given to allow pilots to identify the appropriate time to ‘knock it off’? What simulator and airborne workups were conducted before undertaking this exercise?

One of the purposes of the investigation was to ‘Identify systemic and organisational factors that directly or indirectly contributed to the accident’, yet there appeared to be no analysis of the Unit training and Assessment Plan and its efficacy in ensuring the pilots could conduct the particular mission being conducted that night. The investigation did note, however, that it could not determine what experience either pilot of B83 had in operating a four-aircraft formation. A review of the squadron’s flight programming over the previous years may have provided some indication as to the crews’ experience in multi-ship night formation. The investigation did not appear to review other pilots’ experiences to form a view. “Both pilots had met the Army standards for training for the roles they were assigned…” – yet the question remains, were those standards adequate?

Additionally, it would have been prudent to consider the role of the supervisory chain and the authorizing officer in acting as the final 'gatekeeper' to ensure crews were competent, current and qualified to execute the planned sortie in the conditions expected. An authorizing officer would be reasonably expected to ask questions about how often a pilot may have previously flown in the conditions.

Organization Dysfunction

The report provided ample evidence of dysfunction within the Army Aviation system. For example, between 2021 and 2023, the Army Aviation had over a thousand open ASIRs (Air Safety Incident Reports) each quarter. About 130+ reports were being submitted each quarter. The investigation did not provide an analysis of information held within the ASIRs within the report to provide a picture of any trends that could have signaled deficiencies that may have contributed to this accident. It did, however, identify MRH90 and 6 Sqn Class A and B events in the five years before the accident. It also identified a 2020 report (Levey Report) that identified the potential for ‘normalised deviance’ with respect to risk acceptance.

The report then noted as an ‘indirect finding’ that “Organisational pre-conditions for an elevated levels (sic) of safety risk to personnel arising from MRH-90 operations were understood, documented, communicated and accepted by the Military Air Operator – Accountable Manager”. The report did not explore whether that acceptance was appropriate, nor the accountable manager’s rationale or appropriateness in accepting such risks.

Role of Bushman 84

B84 was number four in the formation and the Air Mission Commander (and Authorizing Officer) for the flight. The Air Mission Commander called ‘knock it off’ to the formation when B83 impacted the water. Yet the report did not explore why B84, who would have been observing the difficulties B83 was having, did not call ‘knock it off’ earlier. At 2.7.2 of the report, the investigation noted the crew of B84 making multiple comments about B83’s sub-optimal station keeping and made an indirect finding following 2.73 noted that “It is very likely that BSMN 83’s CP (FP) was experiencing an increased workload maintaining formation station due to BSMN 82’s CP (FP) having difficulty in maintaining the same plane as BSMN 81.”

The question not explored in the investigation was, why didn’t the Air Mission Commander, noting the difficulties the crews were having and the deteriorating conditions, call off the flight? The report noted that the B84 crewmembers recalled thinking that the manoeuvring was within normal expectations given the circumstances, and that this was a reasonable assumption, “as the CP’s training continuum did not address low level flight formation over water at night.”

Final Word

These are, to me, the more obvious issues with the report and how the analysis appeared to leave more questions than answers. Admittedly, the limitation in this review is that some material was not publicly available, so some of the deficiencies identified may be an unfair callout. Despite the perceived deficiencies, the reader can draw valuable insights and lessons from the factual information contained within the report. I just suggest that the reader examine the facts and review the material emanating from the IGADF inquiry to draw their own conclusions.

The report’s factual information, however, lead me to believe that the fundamental cause of this accident, which was not explored by the report, was the appropriateness and impact of Australian Army Aviation culture. This culture, based on the facts provided by the report, appeared to circumvent or lessen the effectiveness of the airworthiness and safety systems. Army Aviation has overseen several serious incidents and accidents, including a mid-air collision, a ship-deck impact, a controlled flight into water and more recently a ‘heavy landing’ involving a Tiger Gunship. The organization did not address a significant number of reported occurrences prior to the accident. Why the report did not explore the culture more extensively is a question.

Other lessons that should be taken from this report include the value of extensive and in-depth training. Cutting back on training to meet schedules or reduce costs often proves expensive. Exercises and deployment should have extensive workups. The efficacy of the application of the airworthiness system in the Army should be reviewed. Accountable managers must ensure that they properly understand risks – risks that are analyzed, and acted upon, not just accepted, ignored, or forgotten about. Authorizing officers should be encouraged to ask questions to ensure that they are comfortable with the crews’ proficiencies to undertake the planned operations (and unplanned excursions) in the conditions of the day.

Last Final Word

The Australian Senate recently ordered the Australian Government to release the contents of an investigation conducted by the national health and safety regulator (Comcare), which, reportedly, found breaches of the Workplace and Safety Act related to fatigue and the TopOwl system in use at the time.

[1] The Authority is the Defence Aviation Safety Authority (https://dasa.defence.gov.au - Defence Airworthiness Design Requirements Manual Chapter 1). An MTC is a Military Type Certificate and the MSTC is a Military Supplemental Type Certificate.

HOME

HOME