Key to maintaining operational readiness, military exercises are ideally regular but never routine. Combined exercises granted No.3 Squadron RNZAF the opportunity to hone a wide range of operational skills and capabilities in support of a number of different specialist Army units and missions.

Tactical Readiness

‘Steel Talon’ – an annual comprehensive tactical readiness exercise for the personnel of 3 SQN – typically incorporates cooperation with the Army, but this year’s iteration was of a larger than usual scope and was conducted in conjunction with exercises for the Army’s HRTU (High Readiness Task Unit), 161 Battery of the Royal New Zealand Artillery’s 16 Field Regiment, and A Squadron of the NZSAS. Squadron Leader Sam Estall was the exercise controller for 3 SQN and he explained that tying Steel Talon in with the Army’s ‘Silver Scorpion’ and ‘Venom 2’ exercises, after earlier cooperation with NZSAS D Squadron Commandos exercise ‘Saracen’, made for an unusually complex and challenging task. An advantage of being a small country with relatively small military forces however, is that the resultingly small individual units have a high degree of flexibility and can very effectively work together with other small units. 3 SQN, for example, fields the nation’s only military helicopters and its fleet of tactical mediums numbers just eight NH90s.

“This year it just worked out that A SQN was carrying out their ‘Silver Scorpion’ mobility exercise in the Waiouru military training area and HRTU was conducting ‘Venom’. Because there were a bunch of units all doing stuff at the same time, we chose to link up with them in the interests of getting some good missions to fly,” Estall recounted. “Often on Steel Talon we’ll do sorties where we grab some people to support it, or fly with notional troops, but this time it was really good because we could tie in with actual units who genuinely needed helicopter support.” Estall commented that Silver Scorpion was particularly good as it required 3 SQN to carry out a number of different missions that were a mixture of deliberate and reactive taskings, not simply lifting a few troops from A to B. “That meant we could exercise a whole bunch of our skillsets within a fairly busy scenario, with airspace control overlaid on top of it, so it was about as busy as it can get. Variety and unpredictability is important to us, because some of our job is flying pre-arranged, structured missions that we have a couple of days to plan but there are also those times we might be placed on standby in case we’re needed for a time sensitive or reactive mission when someone suddenly needs support, so we have to train for all types of missions and scenarios.”

Live Fire

A SQN conducted live firing during much of their exercise so airspace control was an absolute necessity, with live ammunition in the air for extended periods. “There was a significant amount of ordnance that went downrange so that was awesome,” commented Estall, who added that in his fourteen years on 3 SQN it was the busiest and most complex combined arms live-firing exercise he had seen. “It was just the amount of moving parts and the number of units involved. For example, on the last day we had A SQN conducting a Javelin ambush, supported by HRTU and the fire support group (FSG), 3 SQN in aerial support and 161 Battery providing the ISR (intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance) component. A live-fire exercise will often just be a small, one-day part of a larger activity so it’s pretty rare to see that many units come together to support a whole week of live fire scenarios,” he said. Adding to the risk from live ammunition, UAVs were also active in the airspace at times so the role of qualified JTAC (Joint Terminal Attack Control) personnel was crucial to safe and effective air operation. JTAC monitors all airspace and battlespace activity and directs air operations to mitigate the risk of conflict, while enabling timely, effective mission completion.

The various missions 3 SQN flew over the course of the combined manoeuvres included not just troop transport, but underslung loads, CasEvac sorties, sniper insertion flights, fast roping and other mission profiles as required, with operations initially conducted from the squadron’s home at RNZAF Base Ohakea, followed by a week of deployment to Waiouru for forward operating base (FOB) experience. Although large scale combined force exercises can take a year to plan, Estall advised that planning 3 SQN’s part in these manoeuvres took no more than a couple of months, as the O/C (officer commanding) A SQN had already planned his exercise and could present Estall with a brief of what he wished to achieve, in terms of fitting aircraft into the various scenarios. “This particular one started with them deciding what serials they wanted to create and then us thinking about how we could throw helicopters into the mix. He (O/C A SQN) and HRTU came to sit down with us so I went into that meeting with a list of some of the things I would like to do in order to achieve variety. Within the space of just an hour or so we had an initial plan, which didn’t change much after that short meeting and we were able to pretty much carry it out as briefed a month later. I think that’s the advantage of small unit cooperation. He and I know each other and have been working together for many years now, so we can plan and do something at this level of complexity. We’re both in small units, in an established professional relationship and are just a meeting, phone call or email away. We were lucky that we didn’t really need any specific training serials for 3 SQN, so I just said that he should throw a bunch of stuff at us because I wanted variety.”

Coordination Key

Squadron pilot Flight Lieutenant James (‘Skin’) Erskine was stationed in the SAS field headquarters as Air Liaison Officer (ALO), a communication and aviation expertise liaison between the Army and Air unit command posts. “With his aviation knowledge he could help them shape the mission and feed the subsequent taskings back up to higher headquarters – which in this case was also me in another of my many hats – and then I could generate the task and send it to the detachment,” Estall clarified. “So behind the scenes, he and I were conspiring on what’s happening tomorrow, what’s this going to look like, what do I need to task?” Skin also contributed expertise to JTAC’s airspace control, relaying information on ROZs (restricted operating zones) that sprung up during live firing and helping de-conflict 3 SQN aircraft from UAVs. “That was one of the great things about this exercise,” Estall continued. “We don’t normally have to deal with that type and level of airspace control but there were UAVs and real bullets in the air this time so we absolutely did.” JTAC provided by 16 Field Regiment facilitated airspace control that was successful in ensuring air safety, eliminating airspace conflicts over the battlespace, with assistance from JTAC qualified personnel of A SQN.

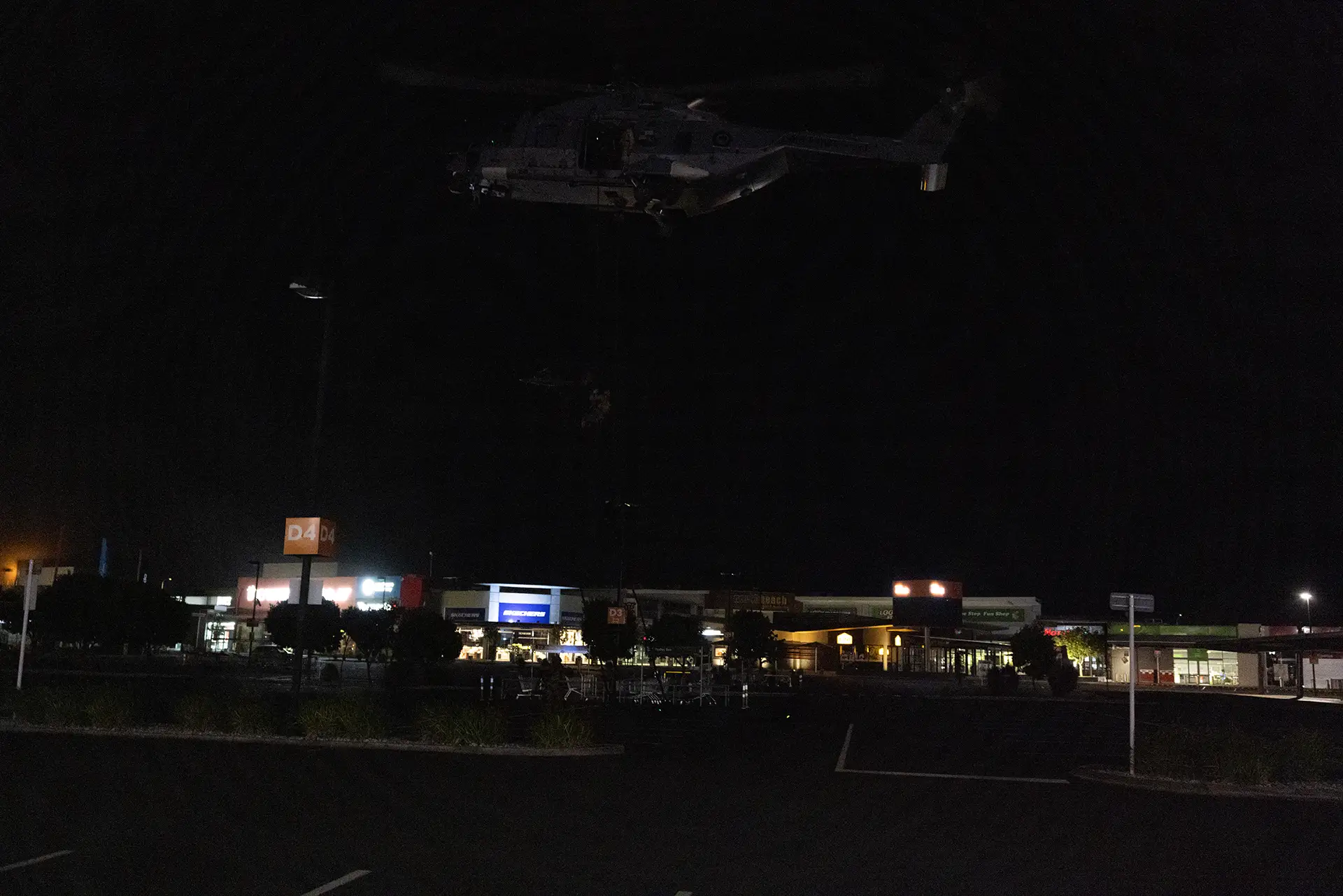

Being both exercise control and an active squadron pilot/flight instructor added to the complications Estall had to deal with. The first casevac mission, for example, was a reactive tasking. As the planner, Estall was aware of that and knew it was coming up, but the crews were completely unaware and he was flying as simulated co-pilot to a pilot under instruction for his B-category captaincy upgrade which is the RNZAF equivalent of “Full Mission Qualification”. “I just did what he told me, when he told me but it is tricky. I was running that side of exercise control and had to have the whole plan in my head. I was simulating the role of our tasking headquarters and had to just task the detachment to be prepared for unspecified support for A SQN, even though I knew it was all scripted. That makes it hard to build a scenario that progresses realistically around that type of no-notice mission, but still allows you to play it through to ensure that it’s all going to work.” Estall also stressed that the seemingly less significant, smaller missions were sometimes among the most complex and difficult to execute. A night-time insertion of a two-man sniper team to a forward location might seem like a minor operation, but remaining covert, in unfamiliar terrain, with low visibility and at short notice, with hostiles in close proximity is far more challenging and complex than a pre-planned three-ship lift and transport of thirty troops.

Estall considered the week of FOB operation out of Waiouru to have been a valuable major addition to the exercise. Although A SQN had requested the FOB deployment to practice uninterrupted full-time helicopter support for an extended intensive unit engagement, it worked in perfectly with the needs of 3 SQN. “We built working out of a deployed location into the exercise, because when you’re at home you can cheat. People go home at night, get distracted, other tasking and routine training is going on in the background. When we’re away the focus shifts though, and it was important for maintenance as well. They wanted to practice operating in the field, detached from the full logistics chain that supports them at home,” elaborated Estall. Maintenance also wanted to test out a deployed aircraft-on-ground scenario and they got their wish, with a couple of outages occurring during manoeuvres that were satisfactorily managed.

Different Roles

Prior to Steel Talon and the combined exercises were typically deliberate, planned missions in support of D SQN and their CT (counter-terrorism) focused squadron-level exercise ‘Saracen’, including several troop transfers and fast roping for a simulated urban assault and a motor vehicle interdiction, among other missions. “Although they are both SAS units, A and D Squadrons have different roles, they work differently and the context is different. If we do all the stuff A SQN wants us to do though, that carries over to what D SQN needs us to do,” Estall advised. He remarked that from the RNZAF squadron’s point of view, Saracen was rather more low-key in regard to flying, as 3 SQN personnel had acquired most of the training they needed during their own recent squadron-level readiness training activity, exercise ‘PekaPeka’. According to Estall, while PekaPeka is obviously aviation focused, it is targeted similarly to Saracen and usually all about 3 SQN crews getting currency and qualification for CT air assault missions, using their A109LUH as well as the NH90s. Because its main mission focus is domestic counter-terrorism however, Saracen presents less planning complexity and mission variety than the combined Silver Scorpion and Venom. It does have its own challenges though, as he outlined, “The tricky thing is that you’re trying to put lots of aircraft into a small space, in complex terrain, on target, on time and without hitting each other so the planning is very much about deconfliction. Flying to a particular place on time is not very difficult, but when that place is a confined area in the middle of a city, it’s at night and you have to make sure you find the right target, get there and not collide with each other, all while everybody is doing slightly different things; that’s a bit more tricky. The hard targets are the ones you’re not going to see until you’re on top of them, it’s late and they’re in the middle of nowhere with no lights around, but they can hear you coming. By comparison, high-rise targets in cities and large shopping malls are usually pretty easy to see, although there are usually plenty of obstacles like power lines and light poles.”

By the end of the multiple exercises, 3 SQN had flown almost all of the mission profiles that Estall had included in his list of desired taskings, including covert infiltrations, deliberate planned air-mobile troop transfers, underslung loads and re-supply, reactive short-notice and no-notice CasEvacs and troop mobility flights. The helicopters even provided recruit familiarisation missions for the Territorial Force, included in the scenario as familiarisation for host-nation forces. Estall loosely described the first week operating from Ohakea as being a series of stand-alone missions generally unrelated to other missions, although still part of the big picture. After the shift to the Waiouru FOB however, the missions became an evolving scenario that built towards shaping the big final push and Javelin missile ambush at the end of the exercise. “That’s where all the moving parts started coming together and HRTU’s tasks began supporting A SQN’s manoeuvre plan. For example, we took the HRTU out to secure a couple of locations, in one of which they were to place the blocking force for the ambush,” he related. It had been intended to also fly the FSG troops in, but the weather became so bad that it was impossible and the fire support component ended up using ground transport. He estimated a split of close to fifty-fifty between air support hours for HRTU and A.Sqn, but more and smaller missions were flown for the SAS, while HRTU’s operations typically called for larger scale air-mobile flights transporting up to two full platoons. After the initial phases, operations converged with HRTU, A SQN and Artillery units linking up for combined manoeuvres in close proximity. Estall considers that concurrent live firing on the helicopter door guns would have been the only additional activity of advantage to 3 SQN crews. “I think we were successfully doing just about everything we can do in 3 SQN as a lift element.”

Estall dealt with the complexities of operating in support of different exercises for multiple units in varying locations at the exercise control level, so his squadron’s flight crews only had to deal with each mission as they were tasked to conduct it, mimicking the reality of a real-world combat situation. “It meant I was running around like a blue-arsed fly, but the crews just knew they had to go out and do this particular job on this day. Anyone can fly somewhere and chuck a rope out the door, but what’s hard as an air mission commander (AMC) is understanding exactly what the ground force commander wants to achieve, and then working out what expert advice is necessary from the aviation perspective to achieve that. It doesn’t sound like much but that’s everything. You have to be an A-category pilot to fill an AMC role because it requires you to be a subject-matter expert and there aren’t many of us on the squadron. Although a ground commander may have an idea of what he wants an operation to look like, he may not know such details as precise aircraft capabilities or operational limitations so I need to have a satisfactorily complete understanding of how the ground troops operate, in order to provide appropriate advice on how to employ the air assets to achieve their aims.” Notwithstanding his planning role, Estall even made sure he was included in some degree of uncertainty, with a CasEvac mission launched on the last day that, although always a possibility, was not pre-planned as he had told the O/C A SQN to just surprise him. He commented that most pilots can relatively easily learn any of the individual skills demanded of 3 SQN’s crews. What an exercise such as this year’s Steel Talon proves however, is whether a crew can cope with the demands of them all, at the same time if necessary and he posed the questions, “Can they fly that underslung load at low level, in crappy weather, in mountainous terrain, with all the airspace control over the top, with the simulated missile threat that requires mastery of all the self-protection systems? Can they do it on time, on target and then do it all again to the same standard tomorrow?”

Working Together

So why is this type of combined exercise so important for 3 SQN? Estall explained, “The whole theme of what we try to achieve with not only this, but with most of what we do, is that this squadron is small and we can’t rely on size, massive firepower, concentration of force or any of those principles to achieve our desired outcome, as we simply don’t have the numbers to throw at the problem. We have to rely on agility, flexibility, decision-making and a very broad skillset instead. We need to be able to do lots of different things, do them when they’re needed and do them well.” He sees squadron training as a large number of building blocks; be it underslung loads, winching, formation flying by day and night, mountain flying or any of the multitude of tasks that a fully competent pilot might be called upon to utilize. “What this has allowed us to do is to exercise as many of those building blocks as possible, in different contexts, in order to achieve our tasks. We weren’t training any new skillsets this time, we were training with all our existing skills and putting them into as realistic a scenario as possible,” he elaborated.

Estall stressed that another major positive outcome is that the exercises demonstrated to all the units with which it typically operates that 3 SQN has the capability to provide and support a wide range of missions that may be required by those units, in almost any theatre of operation. That’s a bit more important for 3 SQN perhaps, than for a unit in a large force like those of the USA. As Estall points out, the squadron is New Zealand’s only Air Force unit that can offer battlefield and logistical helicopter support capability to ground troops. “We’re all they’ve got and that’s the important thing to bear in mind. There’s no one else, so if anyone’s going to do it, it’s going to be us.” He added that 3 SQN is eminently suited to operating with units such as the SAS squadrons or HRTU elements, as the eight NH90s of the small unit are not able to easily carry out such typical larger-force lift tasks as company-sized or larger troop movements. “We can’t train or operate at that level here at home simply because of scale. So we look at what we actually can do at our scale and who we can support. Who needs two or three helicopters, with a wide range of skillsets, that can go and do all this random stuff day or night, at short notice with maximum flexibility?” SOF (Special Operations Forces) support for SAS squadron-sized units is therefore the ideal operational focus for 3 SQN. “They need really good support, they usually need it right now and they need you to be able to do lots of stuff.”

All the foregoing points to 3 SQN being perfectly placed to support SOF units and the squadron is specifically designated in New Zealand SOF doctrine as a direct support unit. A direct support unit is required to have a close and habitual relationship with the supported unit, operate to co-authored SOPs and to train together regularly. “Basically that means I have to know O/C A SQN and O/C D SQN, what they want, how they work, how they think and how they talk. Only then can I be an effective direct support element and not just some random that turns up with a helicopter,” Estall concluded. Instead of being viewed in a negative context, the small size of 3 SQN can therefore be seen as a major asset in regard to SOF support, positioning it to train for quality over quantity. The South Pacific region has only two designated direct SOF support helicopter units, 3 SQN and the Australian Army’s 6th Aviation Regiment, so the RNZAF unit is potentially a crucial tactical asset not only for New Zealand, but also to any friendly nation with interests in the vast geographical area. Someone once humorously described 3 SQN as a company-sized unit that everyone thinks is a Battalion, that does the roles of three and a half regiments, with the resources of a flying school. I’d say that that’s actually not that inaccurate and is one hell of a compliment.

HOME

HOME